In the coming spring, the bookbinding department plans to take a trip to England to visit notable libraries, conservation labs, binderies, and equipment suppliers. As this educational trip is outside the normal curriculum and we are responsible for our own travel costs, we have begun fundraising by doing what we do best: making books. This is also an excellent opportunity for us to get some experience in a more production style of working – rather than the single-item focus that our projects usually take.

This year, we created a small “edition” of sewn board bindings to sell at the school’s annual open house and the Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair . This particular structure, designed by Gary Frost, takes advantage of the sewing and board attachment features of the earliest form of the codex but has a final form that is more in-line with a modern case binding. Like the Ethiopian and Coptic bindings that I shared some time ago, the sewn board binding exhibits unsupported sewing, a squareless cover ( i.e. cut flush to the text), and boards sewn directly to the sections. In the Ethiopian binding, the sewing passes through a lacing path drilled through the board, while in the sewn board structure, the covers are composed of folios of thin card that are “sewn to the text as if they were outermost sections of the book” (Booklab Booknote 8, p. 2). Frost (2004) describes the “particular attribute of the through the fold sewing pattern across the entire bound book” as a “secure cover to text attachment”, providing “exemplary docile, flat opening”. This helpful feature provides a “full gutter reveal” so that books with text are more easily scanned or copied, while blank books are more easily inscribed. The textblock of the sewn board structure has little or no shoulder, requiring “no damaging or distorting backing of the outermost gatherings” (Frost, 2004). In addition, the squareless cover prevents the textblock from sagging when shelved upright.

A description of the benefits of the sewn board structure is all well and good – but a description of the production may be more useful to the reader. We began the project by outlining the materials required and individual steps of the project. Each person would make 12 books, and each book required 4 sections of text paper, 2 folios of endsheet paper, and 2 folios of 20 pt board for the covers, as well as filler board, book cloth, and decorative paper covering. Jobs were distributed among the first years: a person was assigned to each board sheer, cutting specific dimensions of paper and board, while another group of students gathered around a large table, dividing up the stacks of paper and folding sections.

Next the folded sections were distributed into even piles, placed between boards, and pressed overnight.

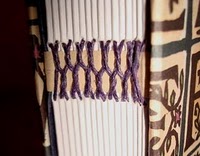

The next day, endsheet folios were tipped on to the outer sections with PVA (polyvinyl acetate) and the sections and boards of each volume were pre-pierced for sewing using a guide. The sewing pattern of 6 sewing stations is the same used for link stitching across linen tapes. The two outermost stations are used for the conventional kettle stitch, while the other pairs of stations provide another link. When the thread exits the section at one station pair, it is linked through the sewing of the lower section, creating a support. The picture below (found at random through the interwebs because I failed to take a decent picture of my own) illustrates the pattern.

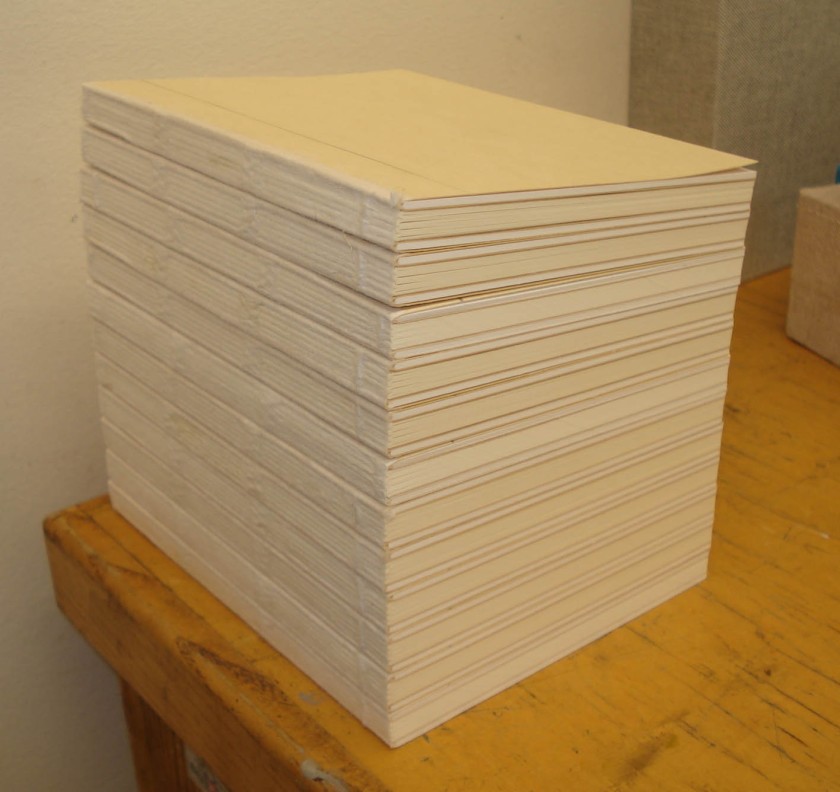

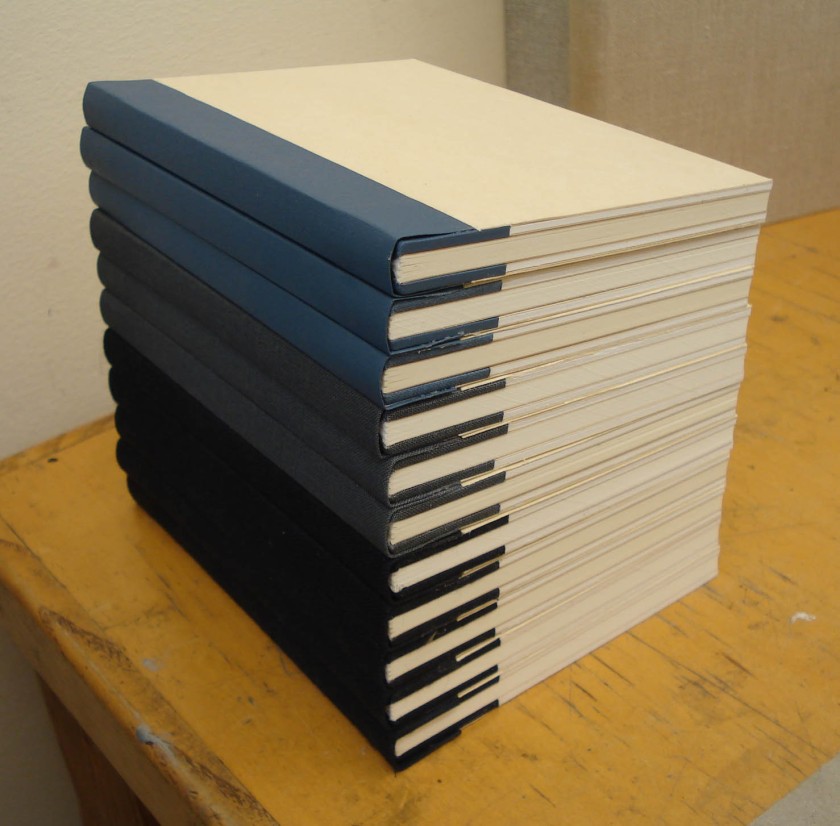

At this stage, the cover folio was also filled by tipping in a 4ply museum board at the fold with PVA. This will make a much thicker (and more pleasing looking) board later in the process. When sewn, my own stack of books looked like this:

The next stage of the process involved lining the spines. Each book was pasted up with Aytex-P wheat starch paste and lined with a piece of Kizukishi Japanese tissue that extended on to each board about 1/8″. Etherington and Roberts (1982) indicate that the purpose of the spine lining is “to support it and to impart a certain degree of rigidity while still maintaining the necessary flexibility for proper opening” and that the “weight and stiffness of the spine lining material is of considerable importance.” In this case, we wanted to maintain the significant flexibility of the structure, so no subsequent paper or textile linings were applied. After lining, the spines look like this:

Up to this point, all of the book structures in the first year curriculum have been methodically trimmed, section by section, before sewing using the board shear. This process takes a considerable amount of time, so for our production project (and in accordance with Frost’s instructions found in the Iowa Book Works Kit) we trimmed the edges after sewing in a guillotine (or “hand lever cutter” – kind of like these). This gives the edges a very even, almost machined look. (When all stacked up, I kind of think they look like a layer cake.)

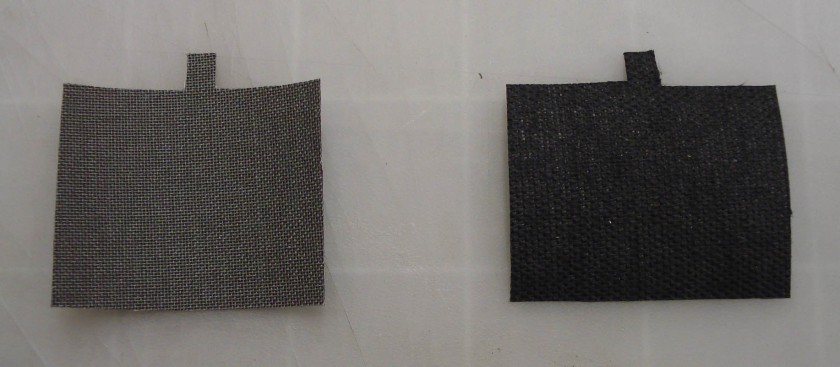

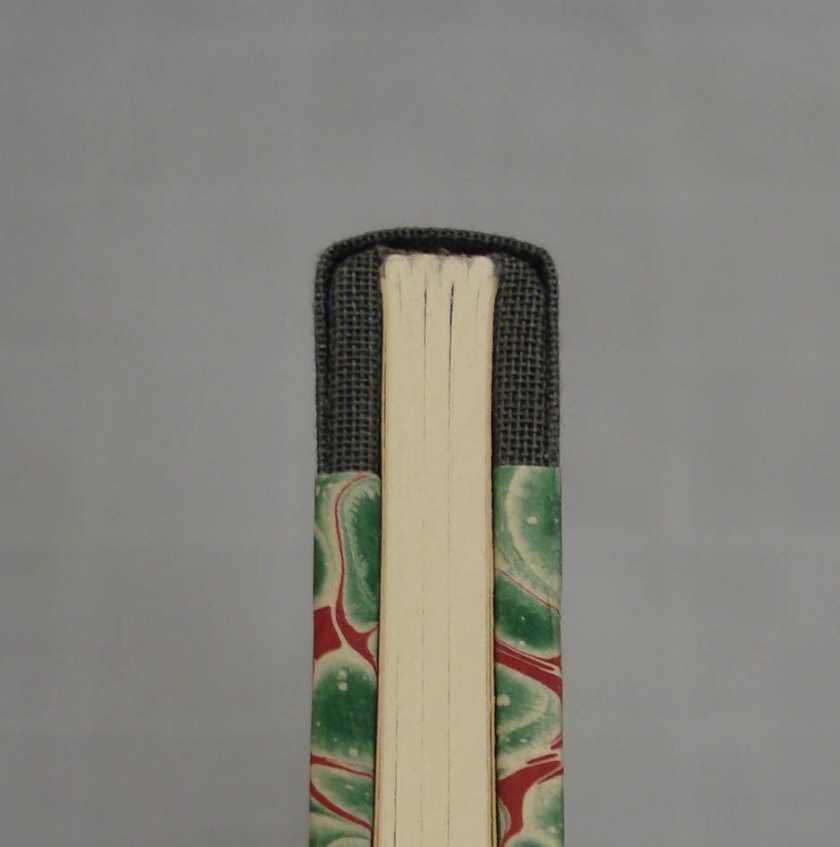

In the next step, little corners of book cloth were adhered with PVA to cover the areas of exposed board at the spine edges of the head and tail.

These add a little refinement to the finished product (as you will see shortly). In this stage, a filler card of 10 pt board was attached to the outside of the cover folios in order to even out the added thickness of the spine covering (that will be added in a later step).

The layers of the covers were then adhered together with 3M #414 Polyester Double sided tape. This allows the layers of board to be laminated together quickly, without the risk of warping from moisture in the adhesive or the requisite long pressing time.

With the boards now solid, book cloth spine strips were adhered with PVA. The spine covering is not adhered completely to the spine, but on the boards about a 1/4″ from the spine edge. This allows for a firm attachment of the material, but without restricting the opening of the book.

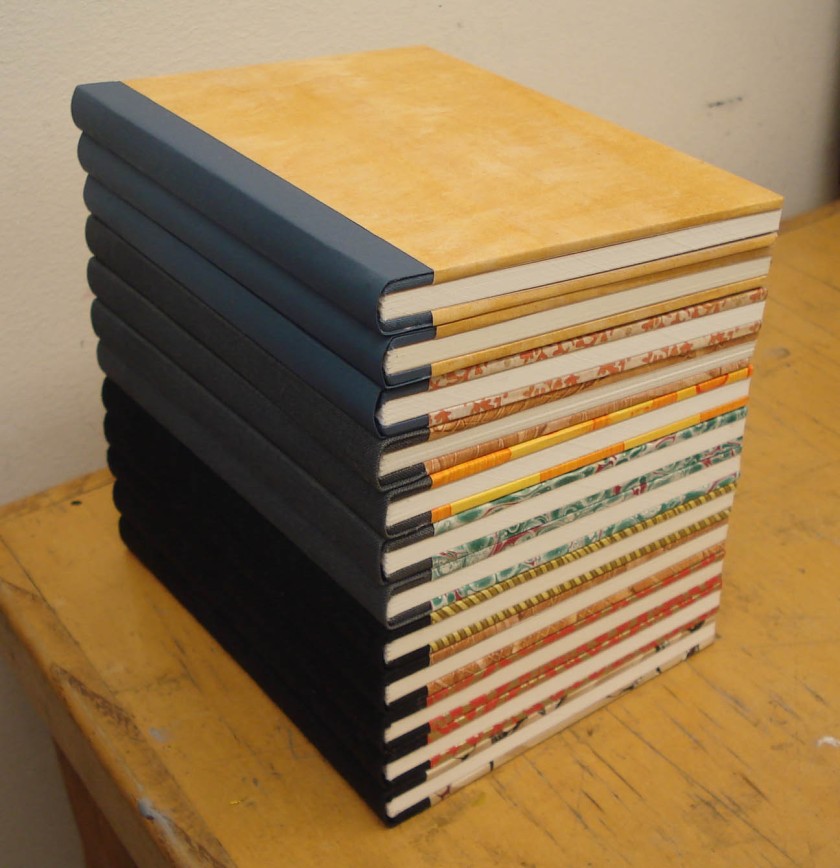

Finally, the books were covered with decorative paper. In many cases, we used paste papers that we had made in class a few weeks before.

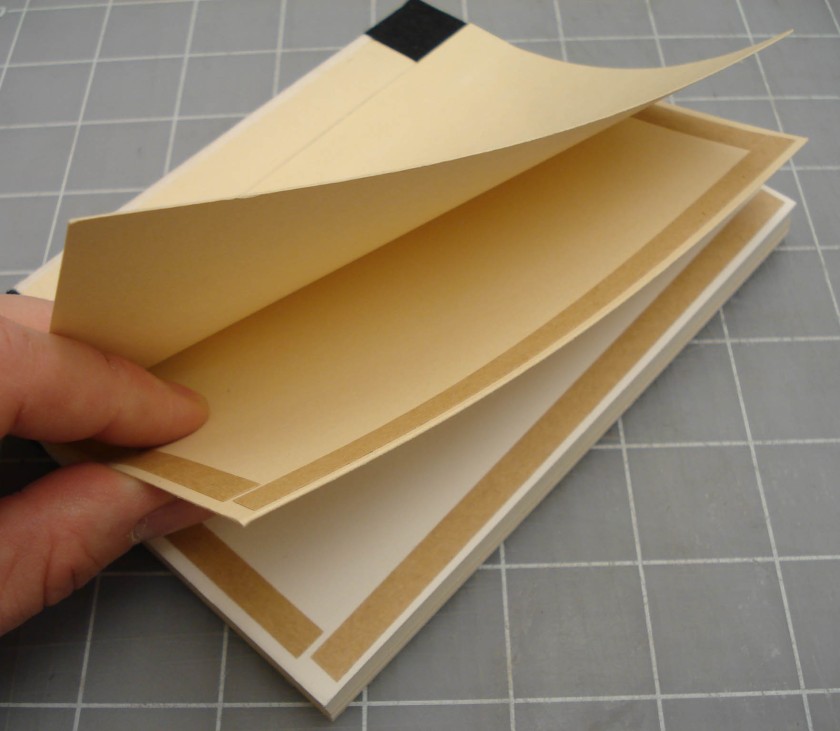

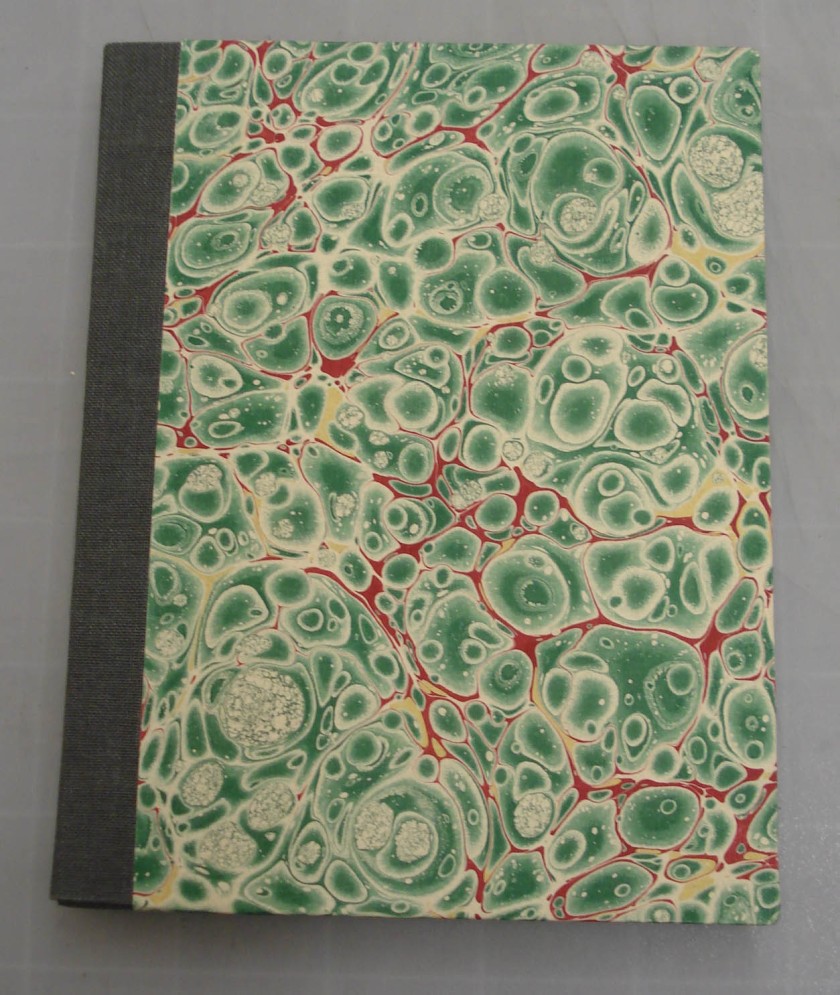

Instead of gluing out the entire sheet of paper, the final board covering is “drummed” on. In other words, the edges of the sheet are brushed out with adhesive and the sheet is applied tightly across the board. Much like the method of board lamination, the drummed on paper allows the boards to be quickly covered while remaining flat. The endsheets are similarly treated; adhesive is applied to only the edges of the pastedown. The result is a thin book with thick boards and a flat spine. Here is an example I made with Italian marbled paper (by Atelier Flavio Aquilina) .

As you can see, the spine tabs and flush-cut boards give the book a very finished appearance while not sacrificing the flexibility of the opening.

Here is a view of the inside “paste-down” and flyleaf.

We had a lot of fun with this project. The sewn board structure is quite versatile and can be embellished with edge decoration and leather spines or simplified according to one’s taste. These books are also easily stamped – the spine can be stamped before being adhered to the board or the covers stamped after finishing. I also really enjoy the way that these books open. I think that I will use this structure for all of my future notebooks. As a conservation student, I will also be on the lookout for instances in which this particular structure might be used as a viable treatment option. I cannot sum up the advantages of the sewn board binding better than Gary Frost (2004) when he concludes, “This book conservation structure is based on historical prototypes, the historical techniques are adapted to contemporary production methods and the specific sewn board practice is directed to the best applications.”

Please keep writing! As a married, gray haired late-comer to bookbinding, it is real treat to follow along as you undertake your studies at North Bennett Street.

Well I’m glad you are enjoying it! I’ve fallen a bit behind in the past couple of weeks because of this set of 12 case bindings that we are doing. But I’ll have something up about that soon enough.

Would love to know what you visited in England. Do you have a list?

Sewn board bindings are great fun to make, and your photos are brilliant examples.

thanks! Glad you like them.