Over the two-year program at NBSS, we make a lot of blank books as models that inform our understanding of the book as a moving system. They give us the opportunity to try out different materials and structures to see how they operate. Most of our models are the same size and use the same textblock paper (which is never true for printed books), and we often vary the sewing supports, thickness of thread, and spine linings for each style of binding. This makes it a bit difficult to make exact comparisons of how those variables affect the book action. One interesting (and quick) project that we did at the end of the first year was designed specifically to compare book action for different sewing structures.

This project is inspired by Tom Conroy’s article titled The Movement of the Book Spine (1987). [Disclaimer: Tom actually taught this as a workshop some years back – both here at the school and other places – so these are based on his design, but may not be exactly as he teaches it.] Conroy’s article attempts to isolate and discuss the variables that affect the action of a codex with a rounded spine, including the supports and sewing, height and shape of the round in the spine, and linings. The introduction suggests that one make a series of binding models “in which only one variable at a time is altered” in order to compare them. Obviously that would be a huge number of models, so our project attempted to do so for just the sewing structures.

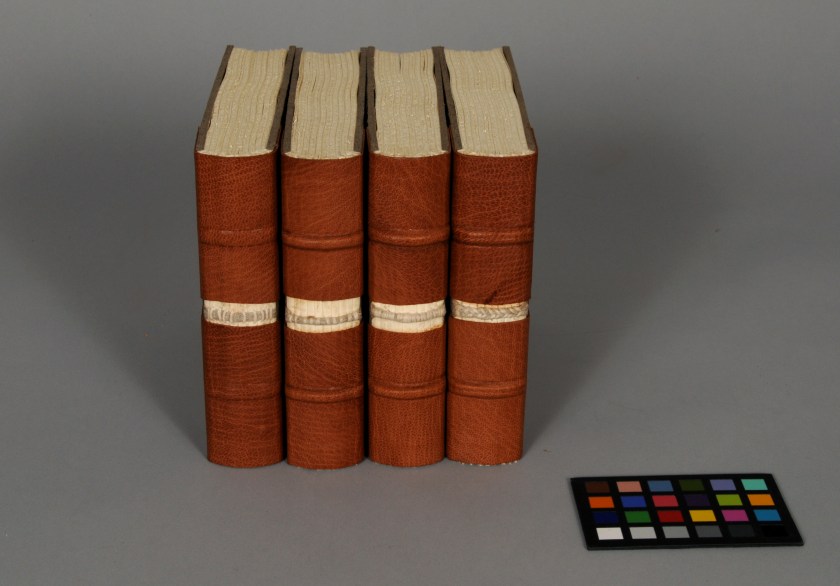

Over the course of a class day, we made a series of extremely rough, tight-back leather bindings. Each binding was composed of the same number of sections, each with the same number of folios of Mohawk paper. The same thread and number of supports were also used for each, but the type of support and style of sewing were varied.

Two basic types of linen sewing supports were used: German tapes and 6-ply cord. One book block was sewn with 2-hole lap sewing over the tapes (above, top). The next was sewn with loops over single cords (below, top). A third was sewn with packed sewing over single cords (below, bottom). The fourth textblock was sewn with a herringbone linkstitch over double 6-ply cords (above, bottom).

Conroy (1987) notes that the tension of the supports will affect both the shape of the spine and the book action (p. 15). Too little tension will leave the book loose and somewhat spongy – causing the boards to skew. Too much tension will put the supports are constant strain when the book is rounded and backed. The effect is more pronounced for thongs (animal) than cords (vegetable), as the cord is less elastic (Conroy, p. 15). All sewing was done on a sewing frame in order to achieve proper tension on the supports. The books were also all sewn in one sitting, compressing each section with the bonefolder as we went, in order to be as consistent as possible.

The spines were all glued-up with hide glue and rounded and backed to get a 90 degree shoulder. Davey board was cut to the size of the textblock.

Conroy classifies the spine linings and covering material of the books as either “tension” or “compression” layers (p. 4). When the book is open, layers adhered directly to the spine will be put under tension, while those further out will be compressed (See Conroy’s paper for diagrams). We often line the spines of our books with layers of textile, paper, and/or leather to achieve the right opening for the size of the book and drape of the paper. Paper (in general) produces a much stiffer spine opening, while leather and cloth are more flexible. In order to simplify the spine lining variable, we finished these bindings as tight-backs with leather as the only spine lining.

Small squares of full-thickness leather were cut for each book, dampened, and pasted out with wheat starch paste. After letting the paste soak in for a couple of minutes, the paste was gently scraped off and a new coat applied. A square of leather was then applied to the head and tail of each book, so that it covered all but the center sewing support. The result is kind of like a cut-away model, allowing you to easily see the sewing structure of each book. Note that there are no headcaps; The leather is cut flush to the boards and textblock, and the boards are not back-cornered. Like I said, these are models are quick!

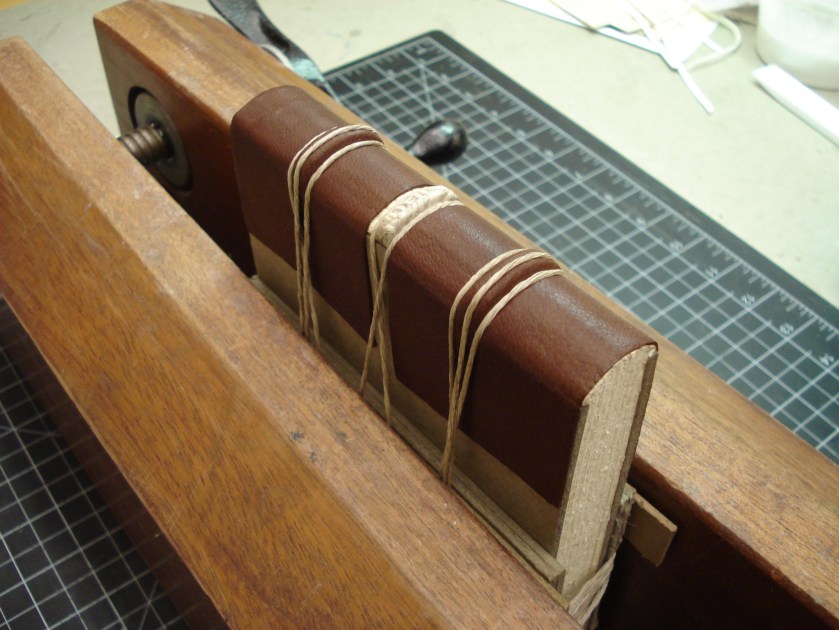

After the leather was applied, the books were tied up in the usual way. A long piece of cord is wrapped on either side of the bands immediately after covering to keep the leather from pulling away as it dried. For the book sewn on double cords, a third wrap was made across the center of each band (see above). We made some rudimentary tying up boards out of scraps of binders board in order to keep the cord from marking the leather that goes across the face of the board.

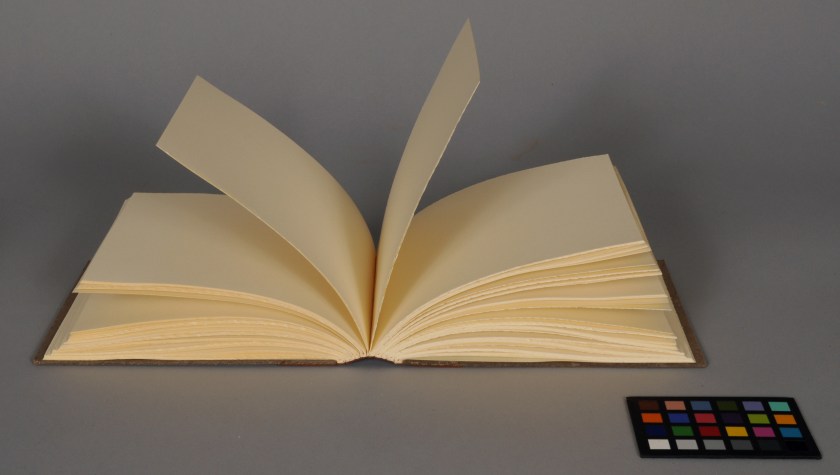

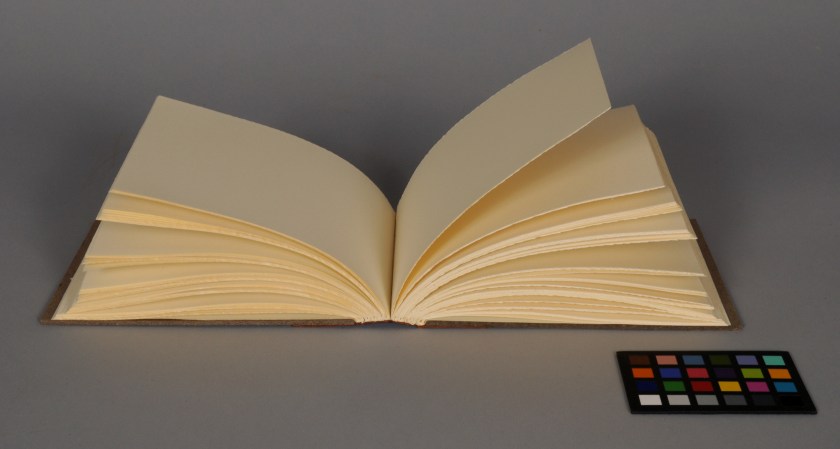

The books were allowed to dry and opened the following day. The pictures that follow attempt to show the different openings for each book. While the results are not so visually dramatic, variations in spine flexibility are easily felt through handling. Note the shape of the spine on each.

The spine of the book sewn on tapes throws up a great deal and opens in a “V” shape.

The book below is sewn on single raised cords (unpacked sewing). It’s spine has more of a “U” shape from the stiffer support, but still exhibits high throw-up.

The book sewn on single packed cords, however, has a very different shape from the one above. The packing of the sewing essentially creates a thicker, stiffer support, reducing the throw-up of the textblock.

Finally, the book sewn on double cords has the least amount of throw-up.

These pictures also illustrate how the movement of the spine affects the leaves. As Mohawk is a pretty stiff paper, less throw up from the spine keeps the pages from lying flat.

Essentially, these bindings show that increasing the diameter (profile) of the sewing support will make it stiffer and reduce the throw-up of the textblock (compare tapes to single raised cord sewing). Also, packing the sewing creates a thicker and stiffer support (compare single cords to single packed cords). Increasing the number of sewing supports makes the opening stiffer as well (compare single to double raised cords). I really enjoyed Conroy’s discussion and many diagrams that illustrate these concepts (p. 10).

But why, you may ask, do we spend all this time thinking about the subtle interactions of the materials that comprise a book spine? A book must function in order to be a book. If it doesn’t open, it is essentially a block of paper; if the sewing and adhesive fail, then it is basically a pile of loose sheets. Books that open well, without creating undue strain on the text or covering materials, are more enjoyable to use and will last longer. Whether creating a new binding or repairing a damaged one, by manipulating the sewing, supports, or linings, one can create a customized book action that is sympathetic to the materials. That is just one of the beauties of a handmade book.

Ω

I’ve just shown you some of the roughest looking leather bindings you can make, so next in my next post I’ll go in the complete opposite direction with some pictures of my first French-style fine binding.

____________

Conroy, Tom. (1987). “The Movement of the Book Spine”. AIC Book and Paper Group Annual, 6, 1-30.

Very fascinating! Thank you for the post, I’ve always wondered how different sewing styles would affect a book.

I use wide (1.25″”) strips of thin canvas bookcloth for my bands. I use coarse mull (with PVA) for a backing with no additional stiffener so that my books will lay open. I’m thinking I should try some different stitching patterns to see how it affects the arch of the spine. Thanks for the very good photos and well-explained demonstration.

Thanks for the comment! There are so many variations that you can use for sewing patterns, supports, linings, and even adhesive. I encourage you to experiment – the differences in book action are really amazing!