One of the staples of my middle school writing curriculum was the book report: I remember regularly being assigned a book on a specific topic and delivering a written or oral summary as a way of testing my comprehension. The book report persisted over the course of my education, evolving into ever more grotesque forms such as the term paper, and in graduate school culminating in the mother of all book reports: the literature review for my masters paper.

While I cannot ever recall particularly enjoying these assignments, I’ve recently begun to appreciate the value of the process of reading and regurgitating. The NBSS Bookbinding Department has an extensive collection of books on bookbinding, conservation, and bookart, and as students we are extremely fortunate to be able to borrow items from the library to read in our own time. While we are regularly assigned reading about particular book structures or binding techniques as a way of informing in-class demonstrations and discussion, our assignments only cover a small portion of the available literature on a given topic. The blog of the Emerging Conservation Professionals Network of the AIC has recently been doing a series of posts around ‘Tips for Becoming a Conservator’, and this week’s tip #7 suggests creating an annotated bibliography as a helpful means of assimilating some of the vast array of conservation literature. This struck me as a particularly good idea for this blog; I can share some of the titles that I’ve been reading outside of class and the act of summarizing will hopefully help me to retain the relevant information in the long run. I had a bit of traveling to do over the holiday, so I took the opportunity to plow through two especially interesting volumes (no pun intended).

The first was the fourth revised edition of Bernard Middleton’s A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique with an introduction by Howard M. Nixon and published by Oak Knoll Press. (Available for purchase here.)

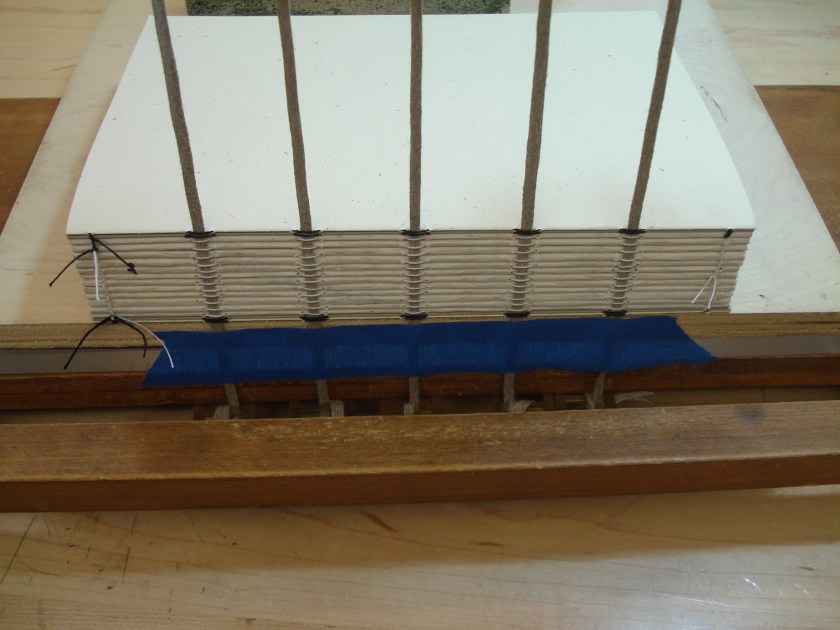

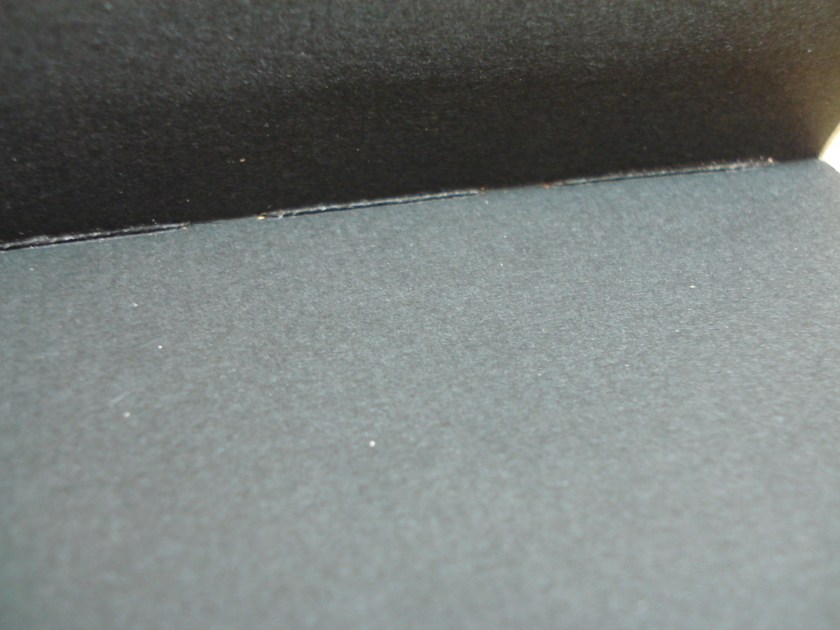

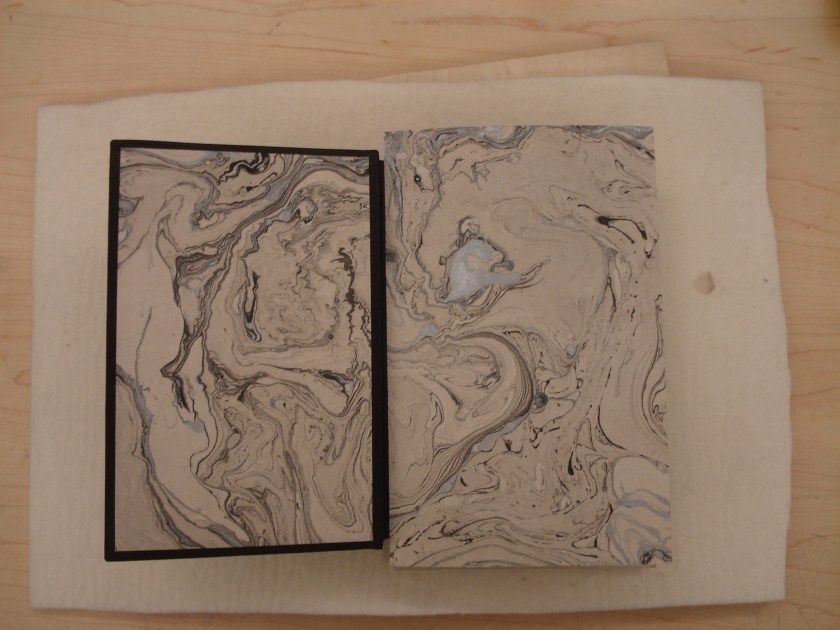

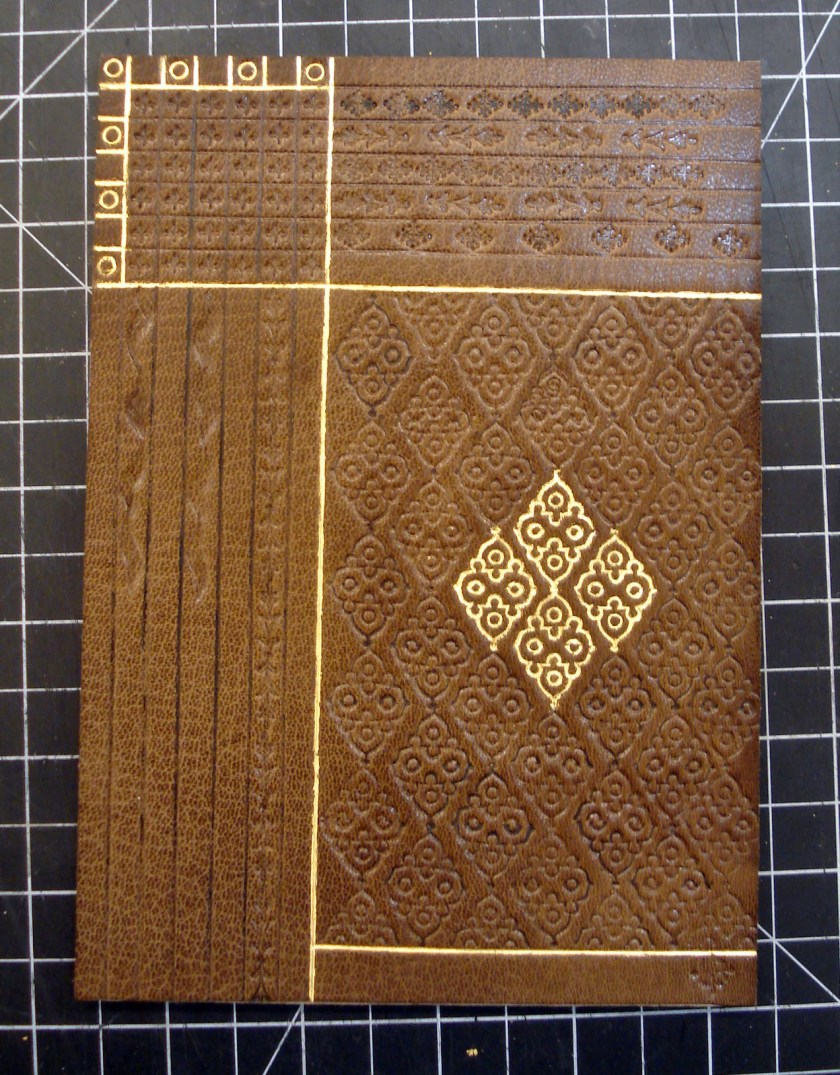

Originally published in 1963, this book is a general manual and history lesson in English binding. Middleton breaks the topic down into 15 chapters that deal with the individual parts of the binding process. For example, chapter one deals with the makeup and folding of leaves, chapter two deals with beating and pressing, three with sewing, four with endpaper structures, etc. Within those chapters, specific structures, materials, techniques, and trends are dealt with chronologically so that one may get a sense of the evolution of the codex in English binderies from the Stonyhurst Gospel to the modern publishers binding. As a supplement to his detailed written descriptions, Middleton also often provides useful diagrams of individual structures. The organization of this book was especially helpful for me at the moment, because it closely follows the organization of the first-year curriculum. As we complete different styles of binding, a great deal of our time is spent examining a particular part of a book’s structure and then preparing several different models to compare the book action or how they perform in combination.

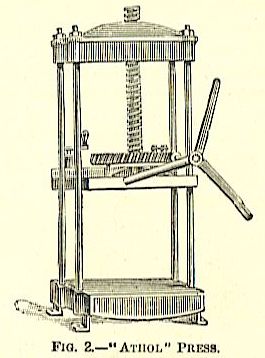

I really enjoyed Middleton’s descriptions and illustrations of 19th century bindery equipment. Much of the discussion is centered around the most common equipment, but there are also some rather novel examples. My favorite is a picture of an Athol standing press from Arnett’s Bibliopegia (1835) like this one…

The fourth edition also includes several fascinating appendices that focus on the income, hours, and working conditions of English trade binders. Middleton paints a rather dreary picture of the typical working lifestyle. For example, the average bookbinder in 1805 worked more than 12 hours a day, 6 days a week, with no running water and the relying entirely on sunlight and candles for illuminating the workspace (p. 261). The author also says that “the majority of the eighteenth-century master binders made poor livings” and that “binder’s wages and hours compared unfavorably with those of workers in many other crafts” (p. 260). I think this information is particularly important to take into consideration when discussing the evolution of popular book structures and materials. Considering the low profit margin of the trade (coupled with increasing literacy and, therefore, production demand), it is no surprise that, for example, the semi-skilled workmen that hammered the signatures and boards (known as beaters) were replaced by massive machine-powered flattening rollers or that leather-covered, laced wooden board structures give way to cloth and paper covered case bindings. Binders struggling to eek out a living were probably always on the lookout for new ways to bring down the cost of production, whether through the division of labor, cheaper materials, or an increasing reliance on machine-powered production methods.

The second book that I picked up over break was the revised edition of David Pye’s The Nature and Art of Workmanship from Cambium Press. (Available through Amazon.)

David Pye was a noted architect, industrial designer and professor of furniture design at the Royal College of Art in London. While the author most often relies upon examples of his own woodworking and various manufactured goods to explore the topic of workmanship, I found it a hugely informative and exacting delineation of terminology that is very applicable to bookbinding. Pye begins with the differentiation of design and workmanship, defining the former as “what can be conveyed in drawings and words”, and the latter as what cannot (p. 17). Pye indicates that all forms of workmanship have two qualities: Risk and Certainty. Workmanship of Risk is defined as “workmanship using any kind of technique or apparatus, in which the quality of the result is not pre-determined, but depends on the judgement, dexterity, and care which the maker exercises as he works” (p. 20). Conversely, the Workmanship of Certainty is when “the quality of the result is exactly predetermined before anything is made” (p. 20). In the most basic form, the operator employing workmanship of certainty cannot spoil the job (such as in full automation), while in the workmanship of risk, the workman can spoil it at any moment (p. 22).

Pye uses the example of the manuscript vs. the printed page to further outline the distinction. The act of writing with a pen is entirely the workmanship of risk, while the workmanship involved in printing is that of certainty. One should note that workmanship of certainty originally involves more judgement and care than workmanship of risk. In the case of printing, the type must be cast, the text typeset, and locked up in the press, etc – but that care is effectively stored up in the preparation and then unleashed in the form of many duplicate pages (p. 21). A form of potential energy in manufacturing, if you will. Text composed on a typewriter is an example involving degrees of both risk and certainty. As the author says, the operator can ruin the job in a variety of ways, “but the N’s will never look like U’s” (p. 21). One can determine the type of workmanship (risk or certainty) by asking the question, “Is the result predetermined and unalterable once production begins?” (p. 22).

Pye asserts that the terms ‘handicraft’ and ‘handmade’ are historical and social, rather than technical terms (p. 26), reasoning that the qualities of risk and certainty are entirely independent of whether the work is done by hand or with power tools. Using the example of a hand-powered drill in a jig in comparison to an electric drill guided entirely by hand, Pye concludes that there is more risk inherent with the unguided power tool (p. 25). The author does suggest that the term ‘handiwork’ should be “confined to the work of a hand and an unguided tool” (p. 28).

While Pye is of the opinion that workmanship is increasingly bad and manufacturing is increasingly accomplished through mass production, he states that “the deterioration comes not because of bad workmanship in mass production, but because the range of qualities which mass production is capable of just now is so dismally restricted” (p. 19). The author also predicts that “unless workmanship comes to be understood and appreciated for the art it is, our environment will lose much of the quality it retains” (p. 19). Quantity production will probably never rely on workmanship of risk again, says Pye, however workmanship of risk will never entirely die out because people will “continue to demand individuality in their possessions and will not be content with standardization everywhere” (p. 23). The author suggests that the danger to workmanship of risk is that “from want of theory, and thence lack of standards, its possibilities will be neglected and inferior forms of it will be taken for granted and accepted” (p. 23).

Considering the current trends in reading and book production, I think those thoughts are entirely appropriate. Poor quality, machine-made paperbacks or case bindings and e-readers will, from here on out, remain the predominant delivery method of text for the average person. But while academics and the media have been heralding the demise of the book since at least 1945 with Vannevar Bush and the Memex, I believe that the codex and hand binding will persist, not only because the form offers more effective text delivery, but because people will continue to demand quality objects that have been produced outside the prevailing outsourced industrial complex. If demand exists in the market for artisanal axes, demand will persist for books. The real question is if as bookbinders, we will maintain high standards of workmanship through professional organizations, investigation into historical practices, academic literature, continuing education in workshops, etc. – or if the public’s contentment with poor quality, non-durable goods brought on by consumer culture will muddle our collective expectations of what a book should be. Ultimately, I am very thankful to be able to participate in a program like North Bennet Street, in which one is forced to grapple with the theory as well as uphold a high standard of practice.