First off, I’d just like to apologize for being such a negligent blogger. The last month has been rather packed with projects, and although a lot has been happening, I have been too preoccupied to share any of it. Therefore I’ll try to give you, the gentle reader, all the highlights in one post. I’ve been listening to way too much This American Life recently, so this installment is organized into three acts.

ACT 1: MARKING TIME

In early November, we took our first field trip up to Dartmouth College. Deborah Howe, the collections conservator, invited the bookbinding department up to Hanover to tour the library’s conservation lab and to assist in the unpacking and installation of the Guild of Book Workers Marking Time Exhibit.

Dartmouth’s campus is stunning and we arrived just in time to see the changing leaves at the height of their transformation. As a southern boy, it is somewhat surreal to be encircled by such intense New England “Autumn-ness”; The old brick buildings and foliage are just so picturesque that they seem fake sometimes. Regardless, the Baker-Berry library building itself is as excellent inside as out; in addition to the well-placed exhibit spaces, the reserve corridor of the library houses Jose Clemente Orozco’s mind-blowing mural The Epic of American Civilization. We were also quite impressed with the size and adaptability of the lab space in Preservation Services.

Shortly after our arrival that morning, the exhibit was delivered in three large crates.

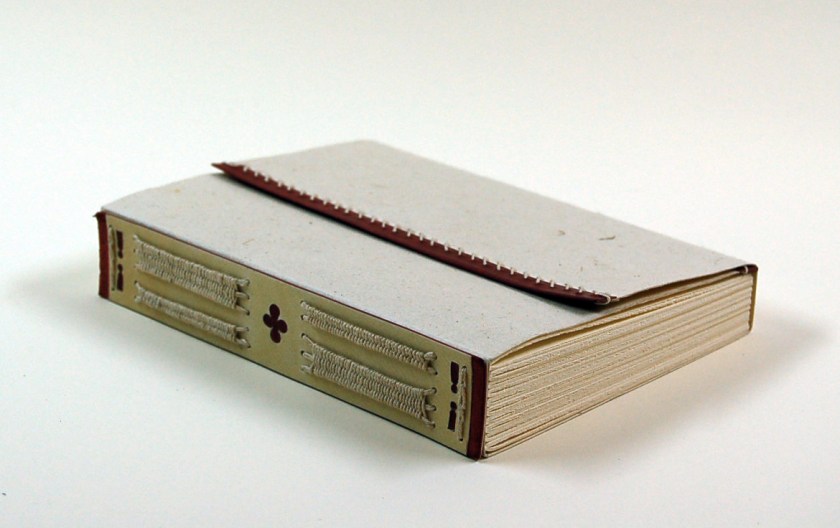

After unpacking the contents of the crates, we arranged them alphabetically by artist on several large tables in the lab. Each exhibit book comes in its own custom enclosure with a condition report and detailed instructions for its display. We broke up into teams and documented the condition of each exhibit item before transferring them to the secure exhibit cases. There are around 50 items, of various shapes and sizes, in this traveling exhibit. To give you an idea, here is about half (in their individual enclosures) spread out on two tables. For excellent photographs and descriptions of the books themselves, please visit the exhibit website.

I really enjoyed the opportunity to experience the behind-the-scenes aspects of a traveling book exhibit. There are so many logistical challenges involved in unpacking and repacking a large group of delicate and valuable items, and it was fascinating to see the solutions employed by the organizers of the show. For example, after determining the best way to pack 50 oddly sized boxes securely in three crates, how does one ensure that they are repacked the same way as the exhibit travels through the eight locations on the exhibit schedule? In this case, each crate included a detailed packing list as well as printed photographs of each layer of boxes and packing materials as they should be placed in the crate. Taken with the packing instructions by each book artist, every step in the packing process is well documented.

In addition to working on the exhibit, our field trip included a brief tour of the Book Arts Program facilities and the opportunity to handle some high spots from the rare book collection. The special collections at Dartmouth are stored in an amazing climate-controlled glass cube!

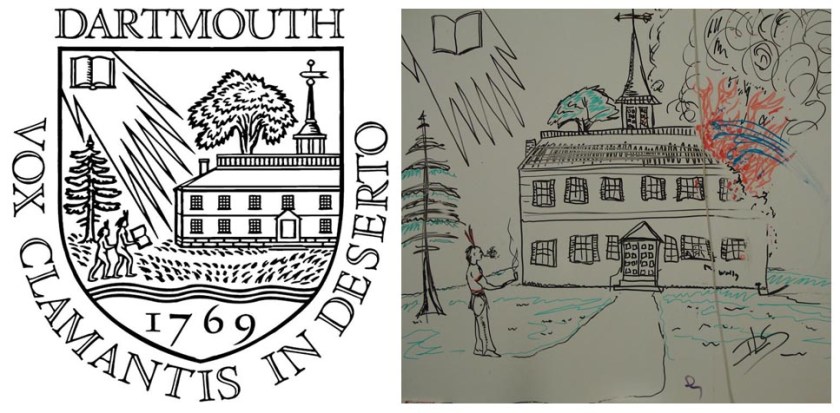

But aside from book things, as we wandered through the campus I managed to snap some photos of two particularly amusing examples of Dartmouth student humor. The first is an re-imagining of the Dartmouth shield by an anonymous artist on the white board of an empty classroom.

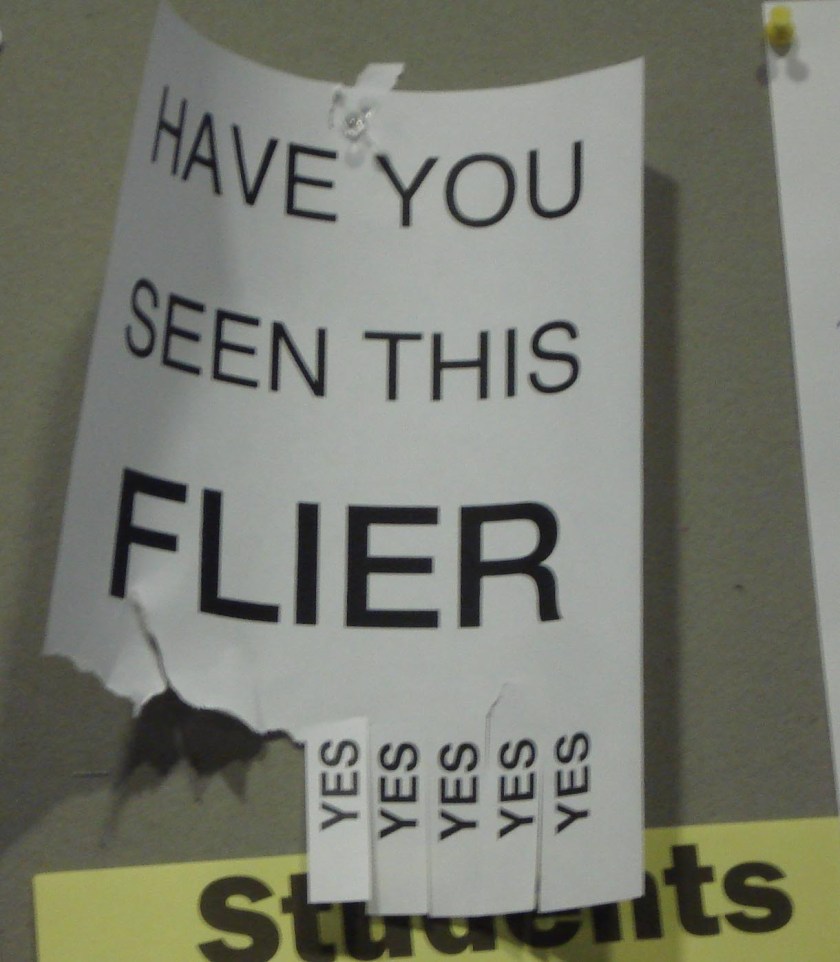

The other is a flyer posted on a bulletin board in the cafe area of the library.

All in all, our outing was an amusing and edifying experience. Special thanks to Deborah Howe and Jay Satterfield for taking the time to make our trip so enjoyable!

ACT 2: GRAPHITE EDGES

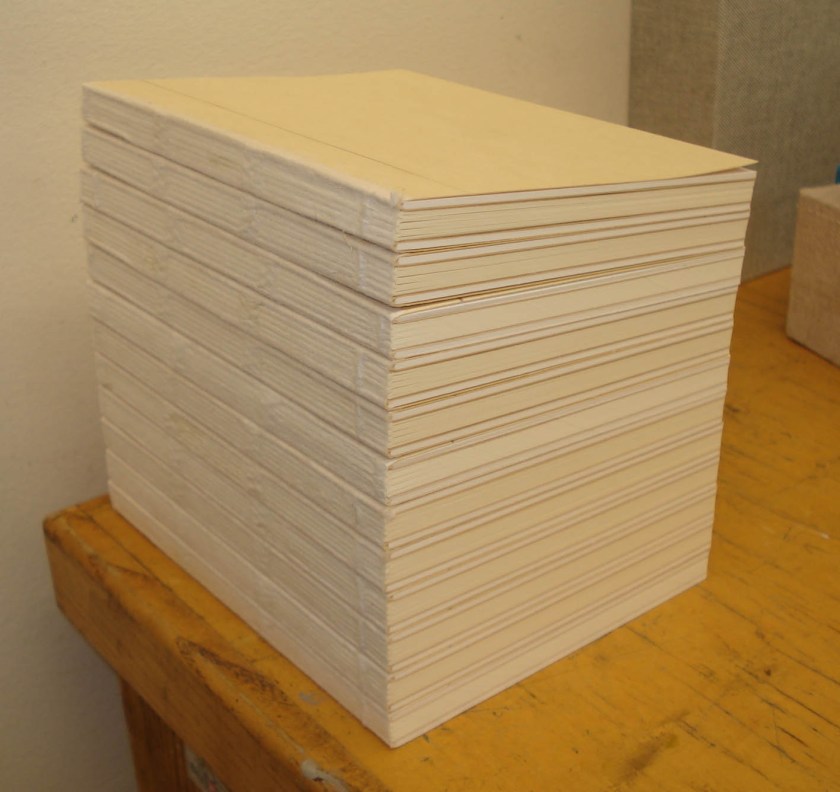

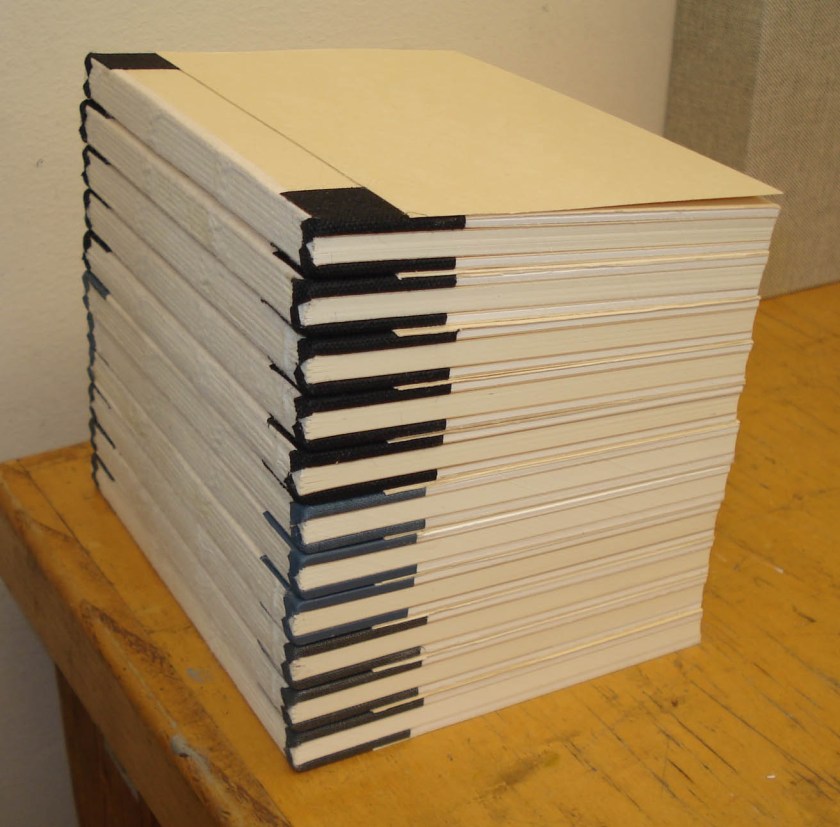

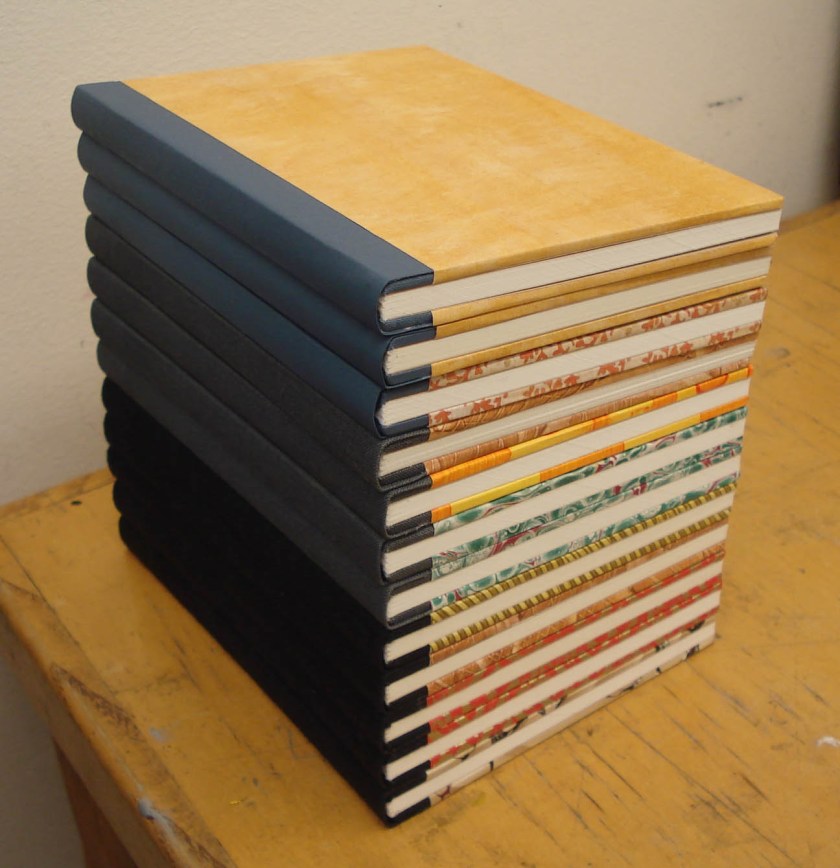

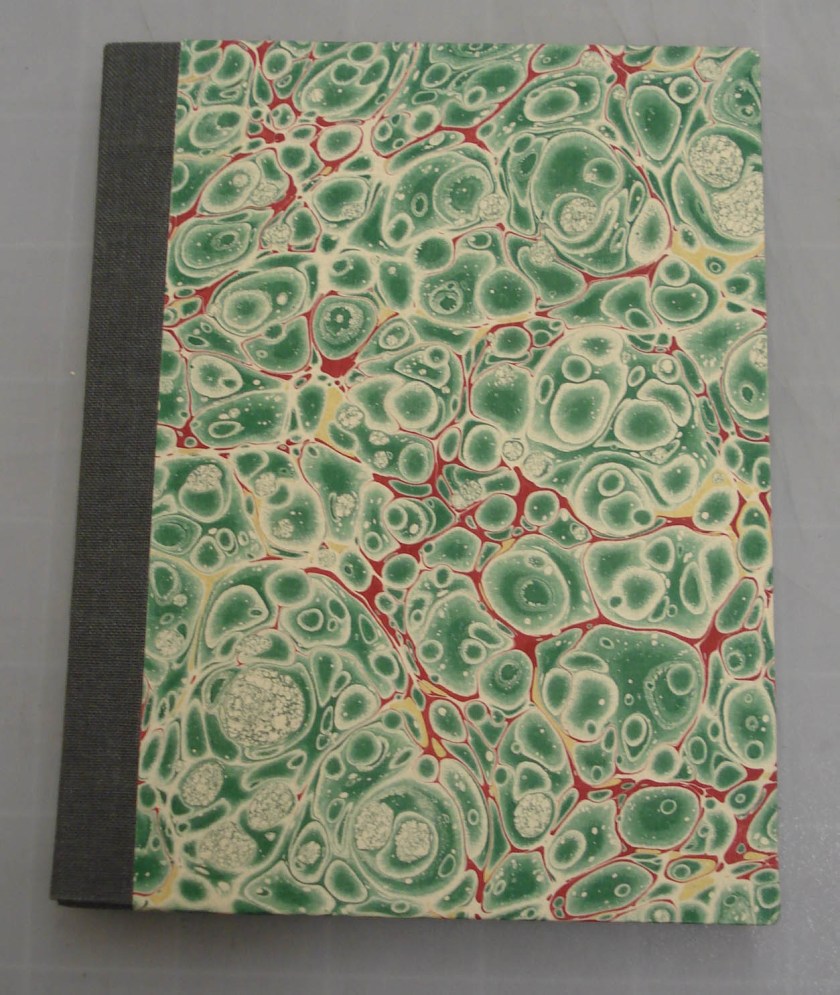

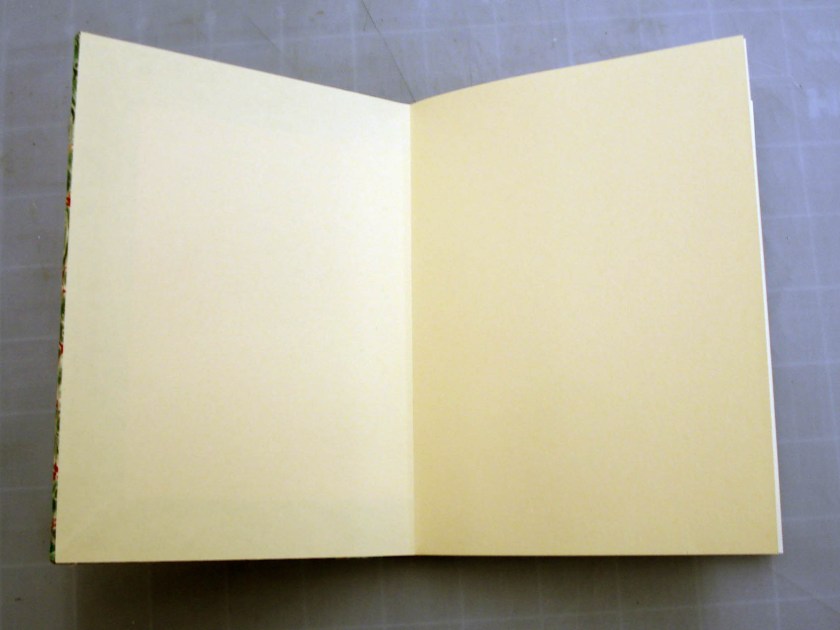

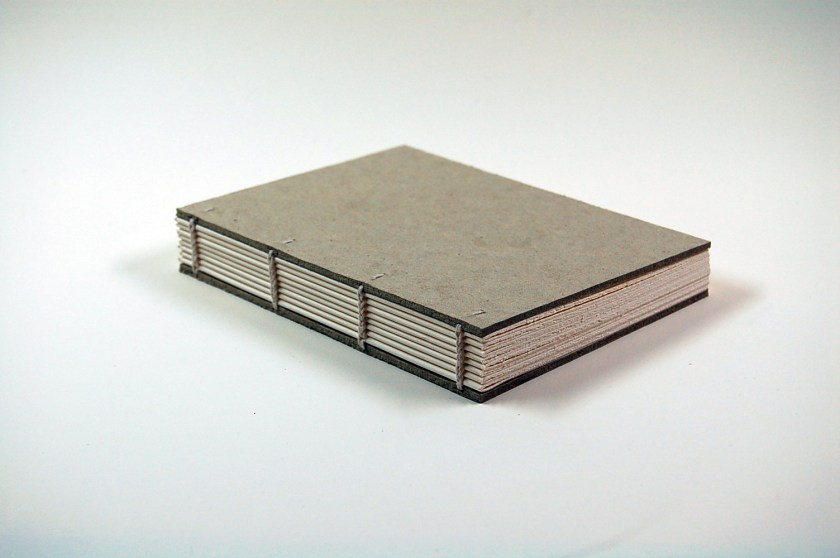

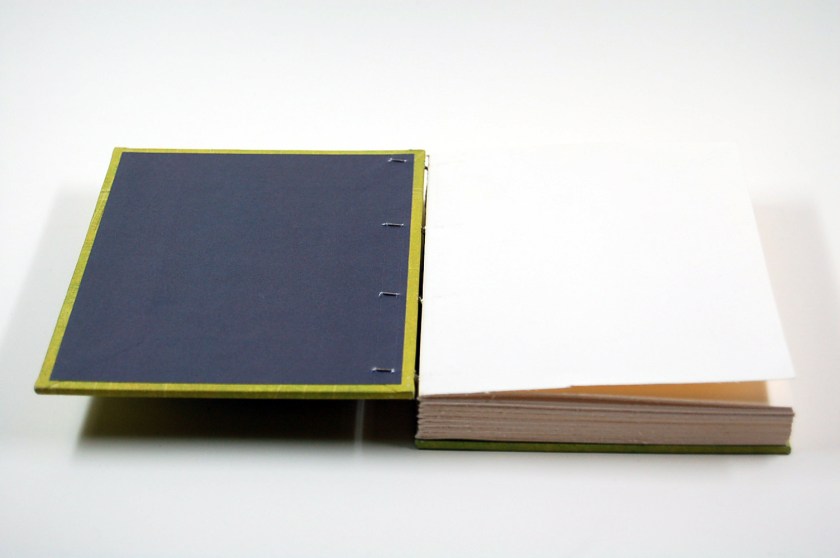

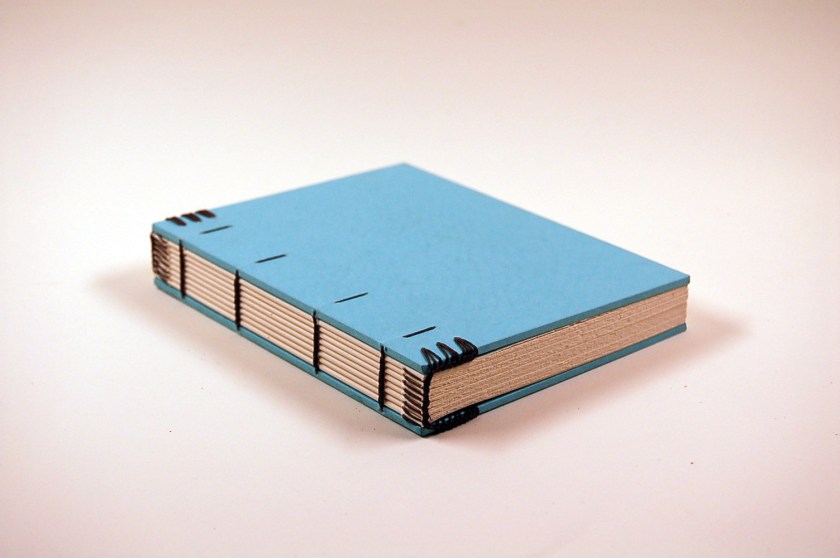

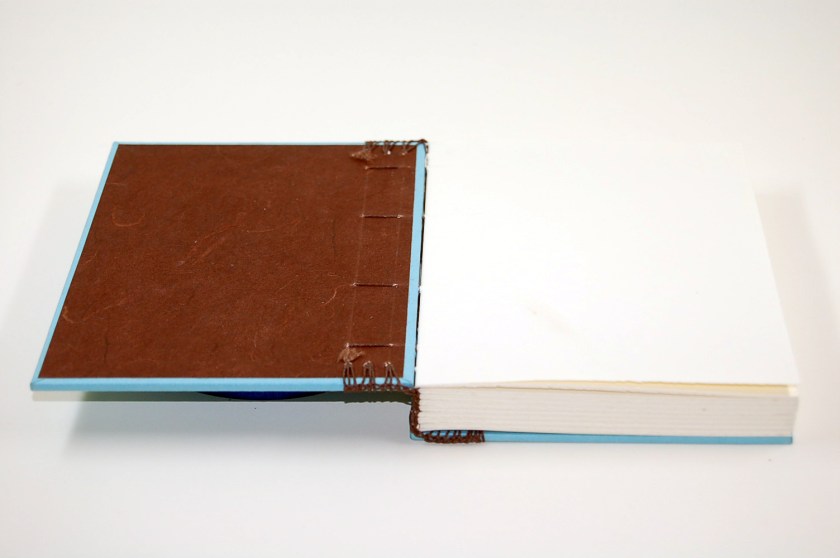

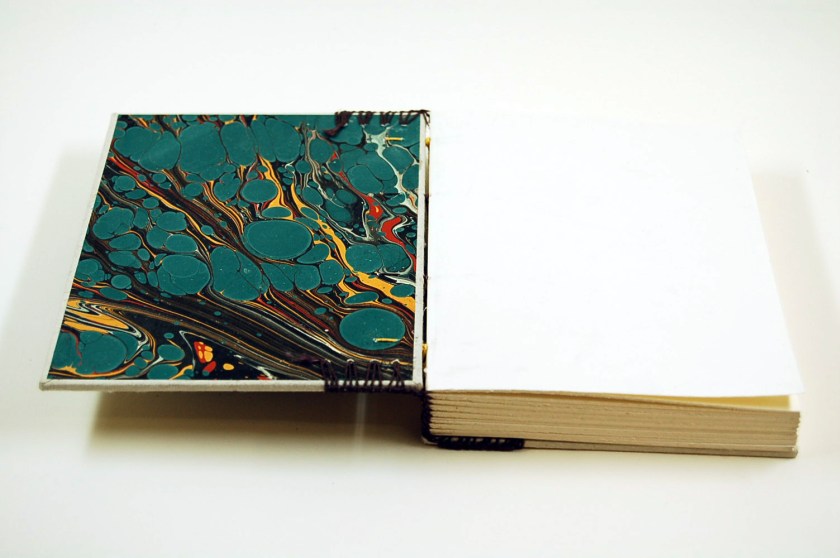

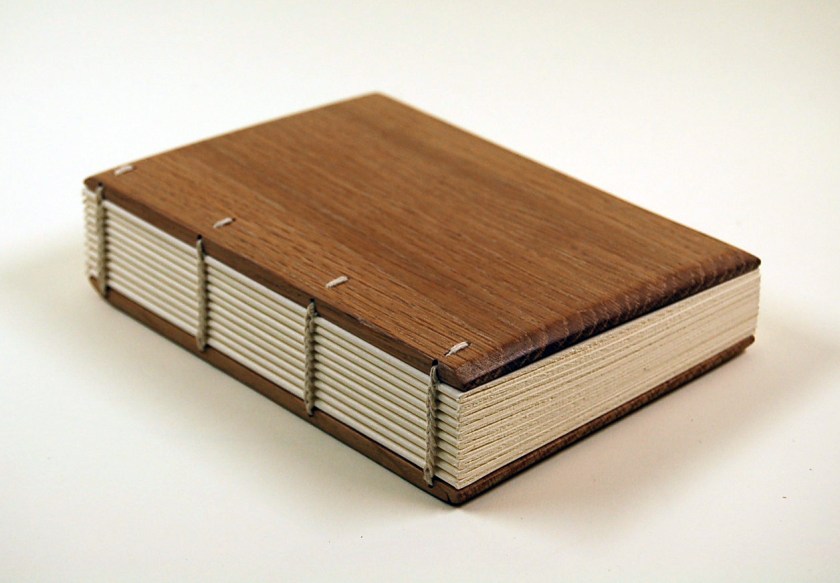

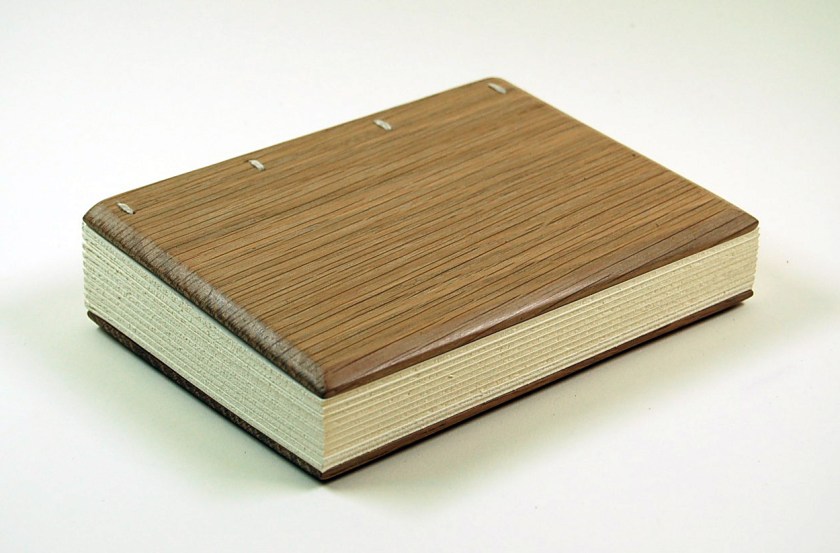

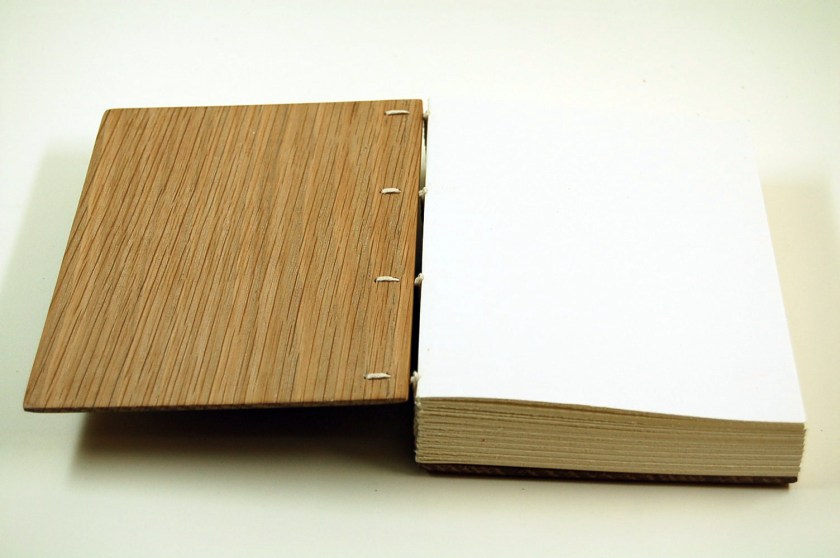

As I may have mentioned before, one of the current projects in the first year is an “edition” of 12 case bindings that exhibit common materials but very in case style, endpaper structures, headbands, stamping, and edge decoration. I should be finishing this set this week, and will post pictures soon. In the meantime, I wanted to share some edge decoration that I think is very cool.

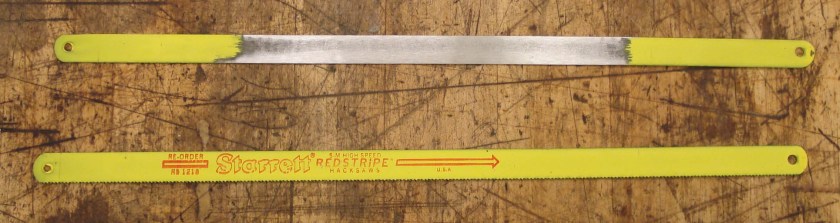

With a bit of nagging, we got Jeff to demo the proper operation of the plow and edge treatment with graphite. The plow is a device used for trimming a very smooth edge on the textblock. Etherington and Roberts describe the plow as such:

“It consists of two parallel blocks of wood about 4 inches wide and 8 inches long connected by two guide rods and one threaded rod, with a cutting blade attached to the lower edge of one of the blocks. The left hand part of the plow fits into a runner on the left cheek of the lying press, while the other block is fitted with the adjustable knife. The knife is generally moved inward by the turn of a screw, cutting into the leaves as the plow is moved back and forth.” (under “Plow“)

At NBSS, we have a very nice plow and lying press made by Timothy Moore, much like this one:

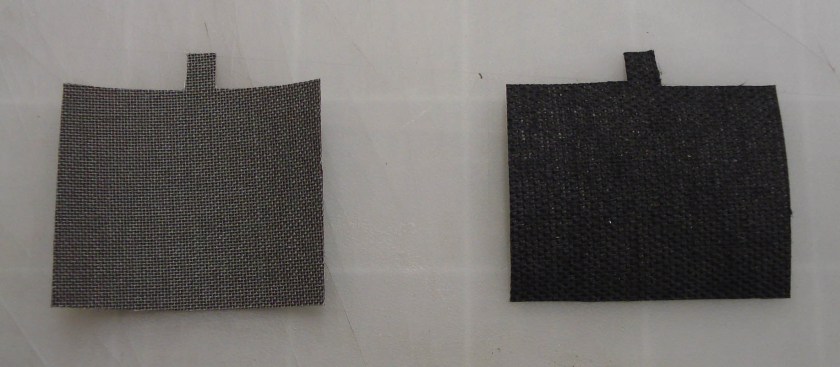

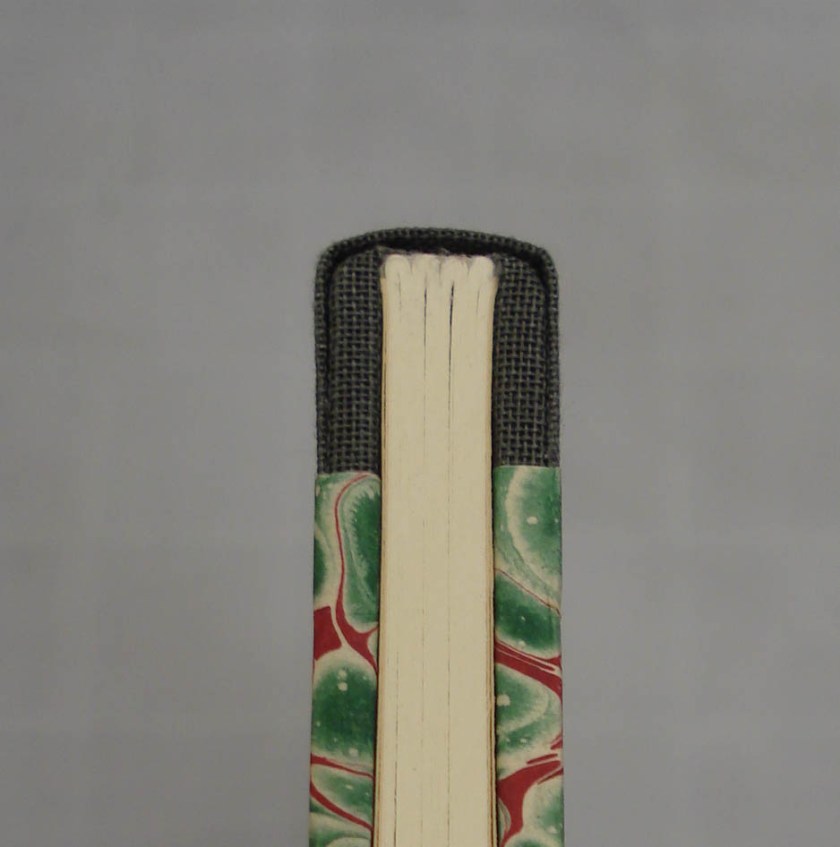

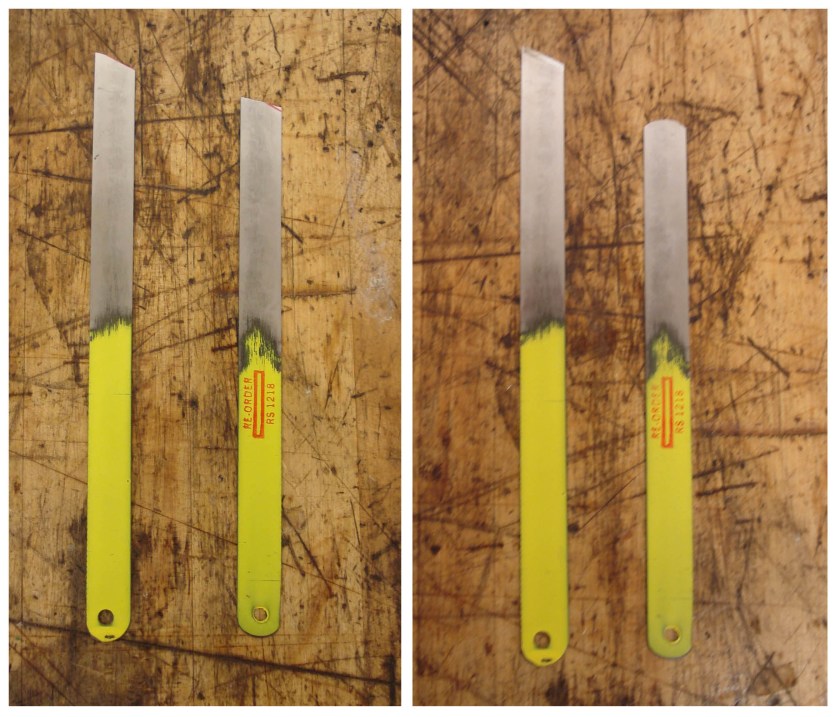

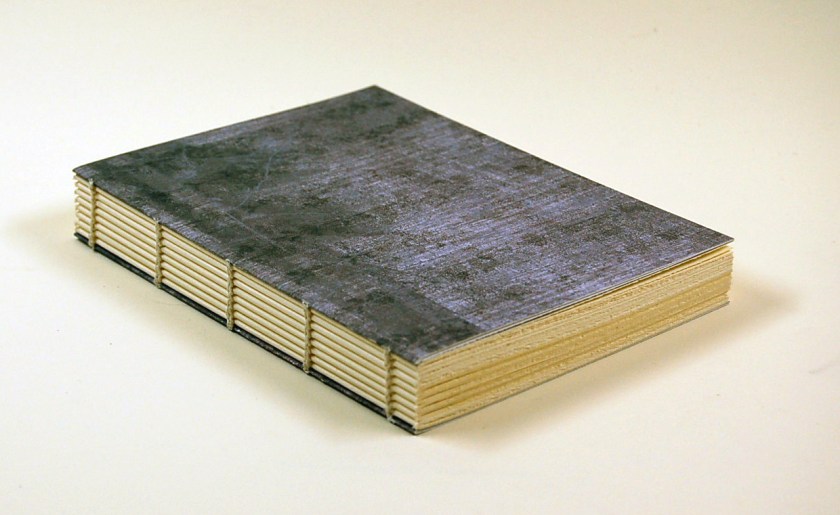

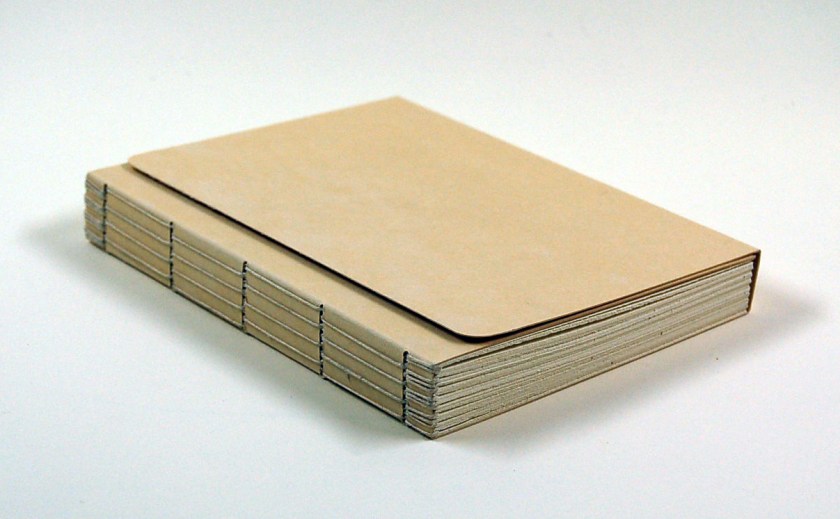

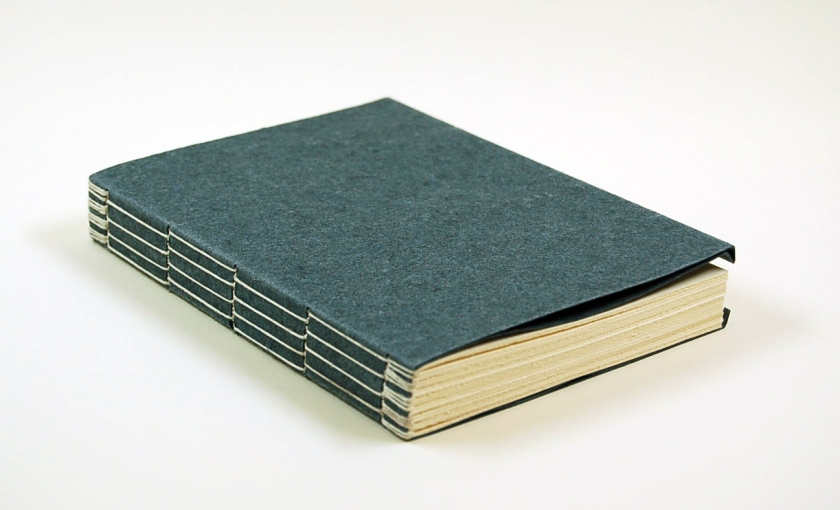

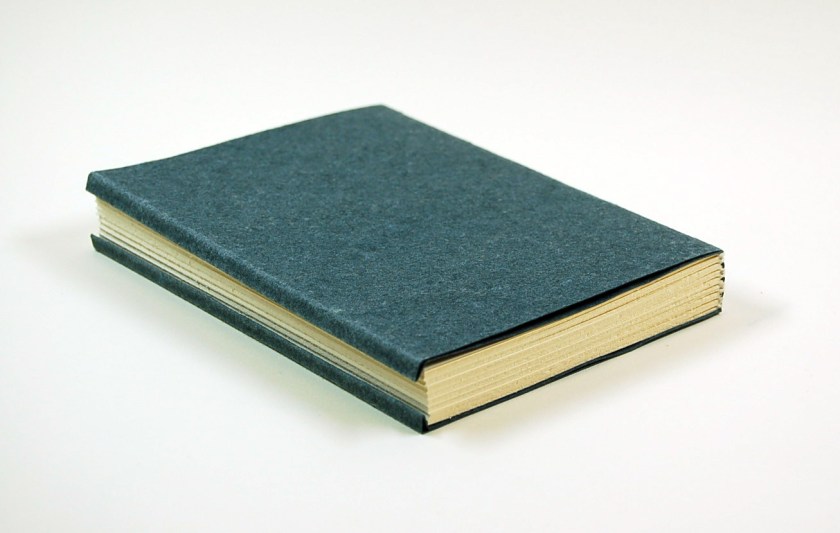

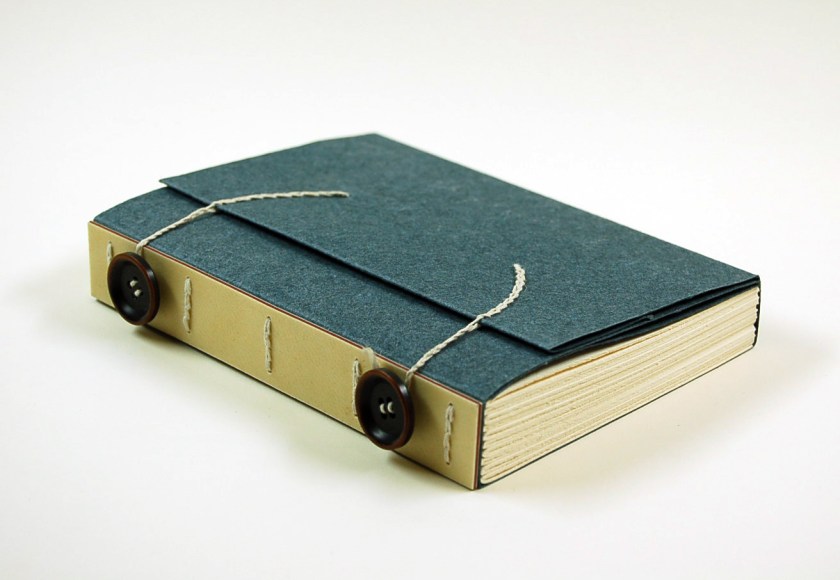

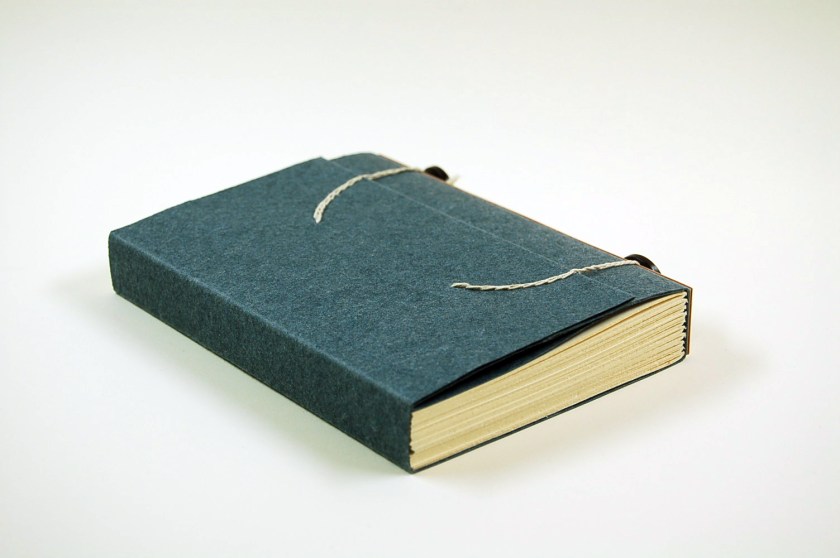

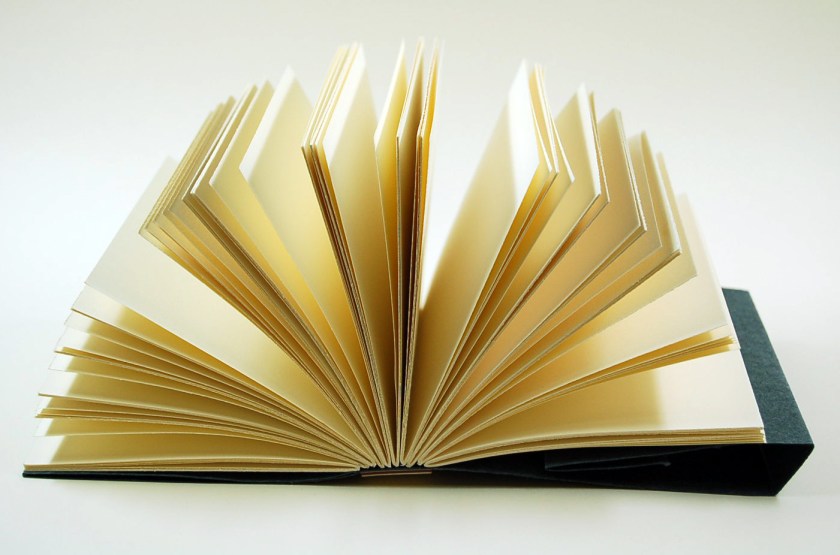

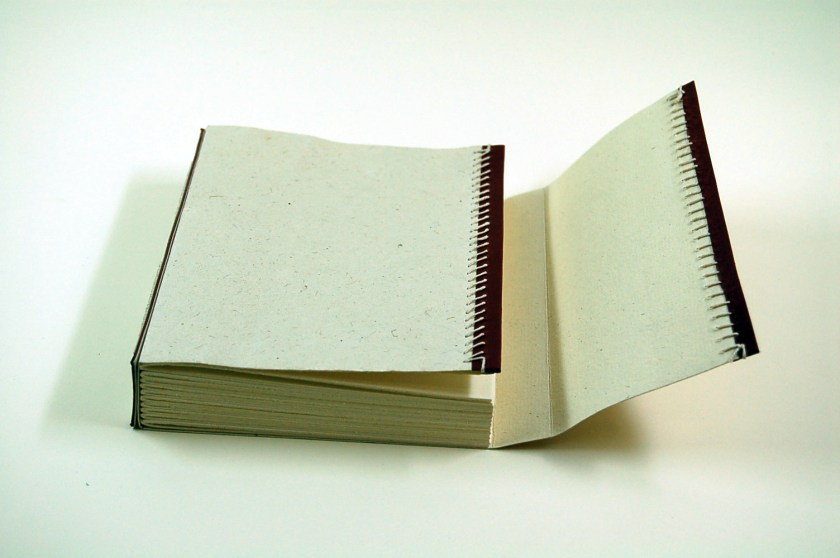

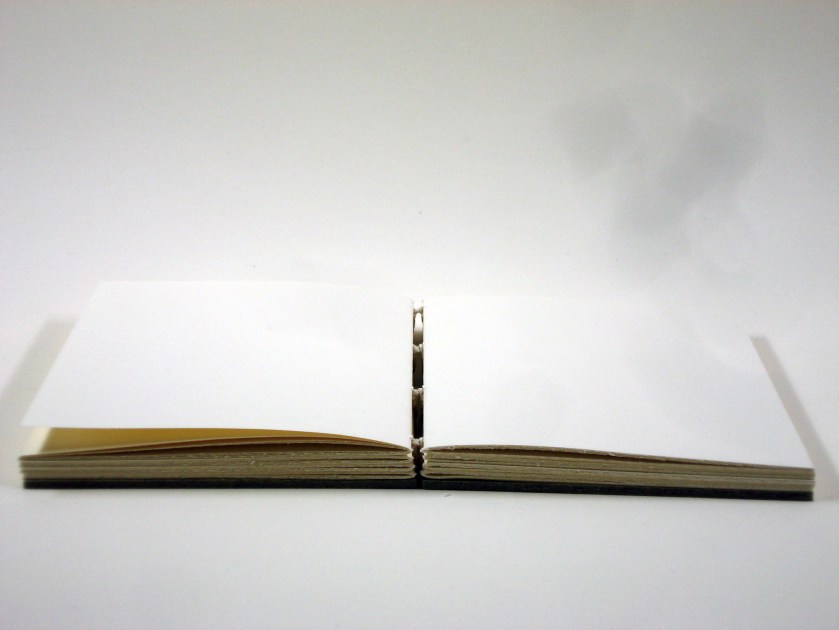

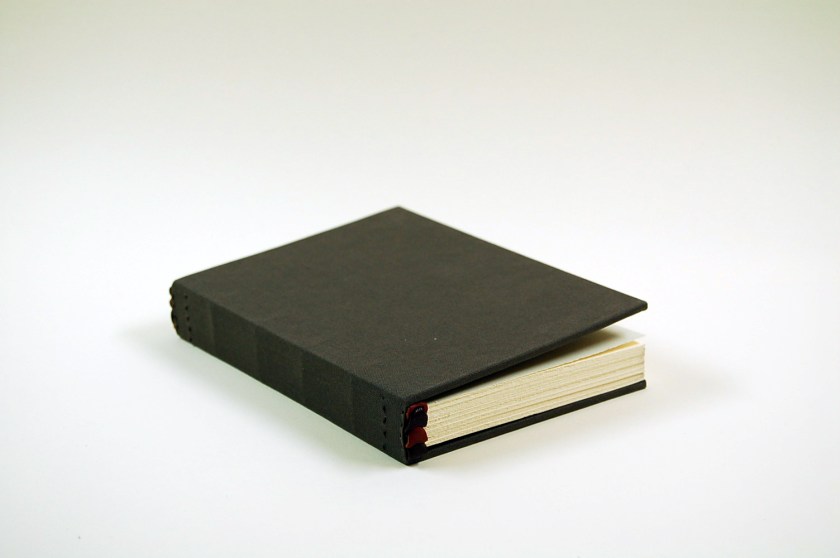

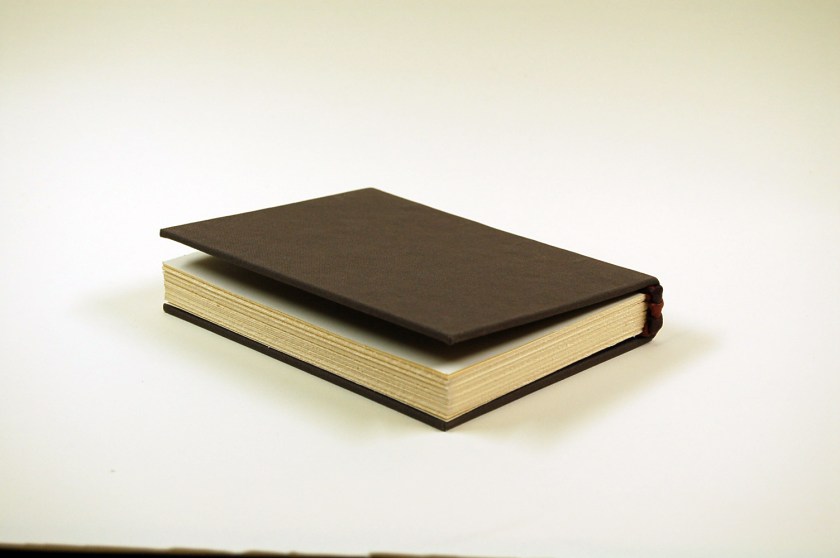

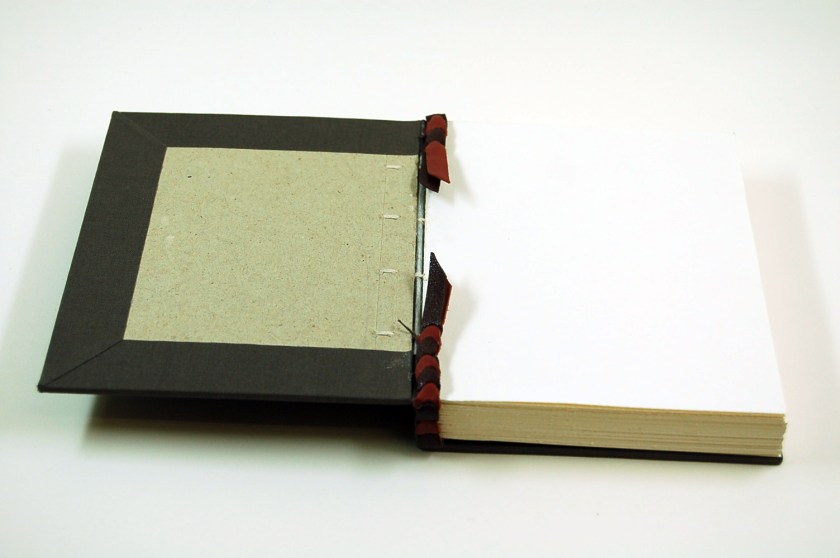

After plowing the edges of a couple of my textblocks, I decided to attempt to decorate the top edges of two with graphite. The process involves sanding the plowed edge to get it very flat and smooth. A mixture of graphite powder and paste is applied and rubbed in with one’s thumb. The edge is then scraped clean again with a metal scraper to really be sure that the edge is smooth and another coat of graphite and paste is rubbed in. After a light coating of bee’s wax, the edge is burnished with an agate burnisher. The result is a dark grey, polished edge.

Graphite definitely gives the edges a very refined look, but it can be quite difficult to achieve an even finish. It is much easier (and cheaper) than gilding, but also functions to create a kind of seal between the leaves and reduce the paper’s exposure to dust and pollutants. Here is a close up image of the finished edge.

After the textblock is removed from the press, one must smack it sharply against the lying press or table surface a couple of times to separate the leaves.

and finally,

ACT 3: BOOKBINDERS MAKE MORE THAN BOOKS, APPARENTLY.

I had never heard of this restaurant/food product before Daniel brought it in the bindery the other day. I think it’s hilarious. You can read more about good ol’ Samuel Bookbinder (complete with jazz sax soundtrack) here or here.

That’s all for this installment. Next up, the return of the medieval linkstitch, the Big 12, and more!

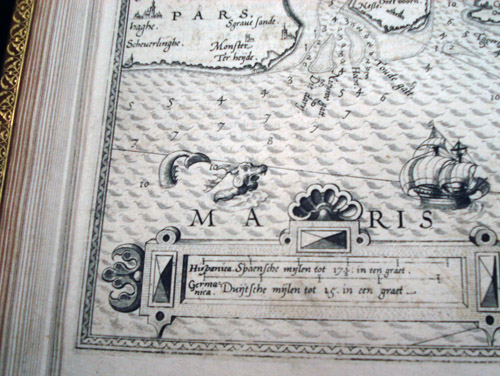

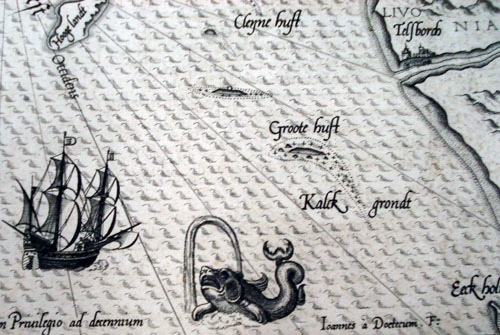

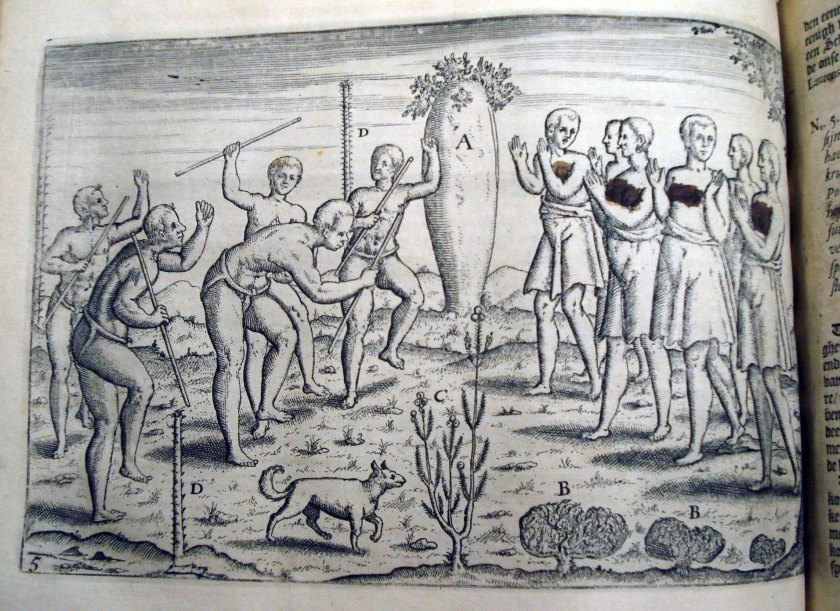

On certain pages, offending images are gone. I cannot determine if they were physically removed from the page by the censor or if this is the result of

On certain pages, offending images are gone. I cannot determine if they were physically removed from the page by the censor or if this is the result of