In February and March, the Boston University College of Fine Arts showed works by South African artists in two exhibitions celebrating the Caversham Press. Founded in 1985, the Caversham Press was created to give South African artists access to a professional and collaborative printmaking studio. Featuring over 120 works by 70 artists, the exhibition titled South Africa: Artists, Prints, Community, Twenty Five Years at The Caversham Press celebrated Caversham’s history and the diversity of South African printmaking. You can find a short article with a digital slide show here and the original press release here.

A central figure in the early years of the press, William Kentridge was also featured as the seventh annual Tim Hamill Visiting Artist Lecturer and in a concurrent exhibition, titled Three Artists at The Caversham Press: Deborah Bell, Robert Hodgins and William Kentridge. As a side note, Kentridge also directed War Horse, an adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s World War I novel, currently playing at the Lincoln Center Theater in New York. While I haven’t yet seen the play, I recently watched the TED talk featuring Basil Jones and Adrian Kohler of Handspring Puppet Company and thought it was absolutely amazing.

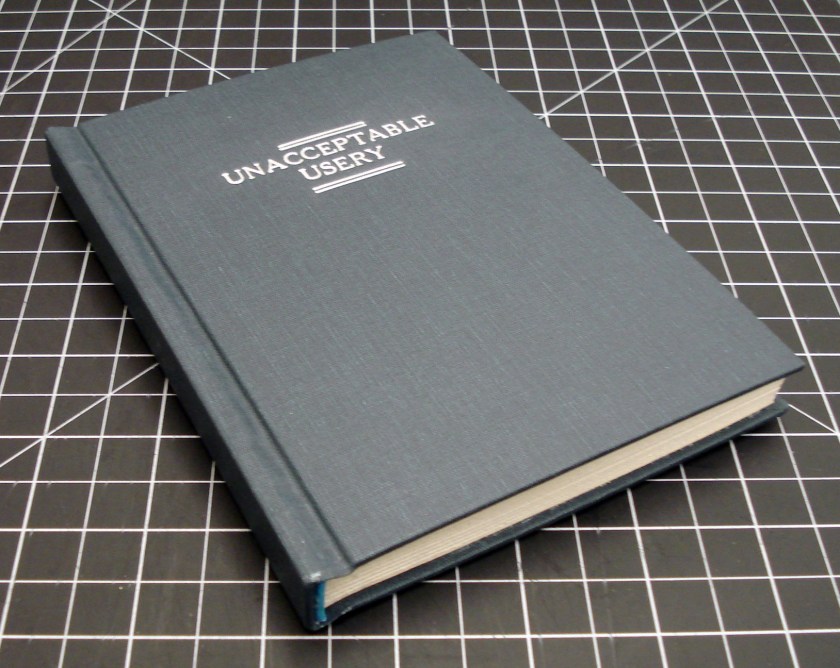

But what does all of this have to do with bookbinding? As part of the exhibition, our program was approached by BU to create a number of large, custom portfolios for selections of prints from the show. This project gave us an excellent opportunity to experience the particular challenges of designing and completing a larger production project. The initial design called for a cloth-covered portfolio with three flaps to hold the prints, all enclosed in a case secured with ribbon ties.

While there are a number of ways to fabricate an item like this, the design of this particular portfolio had to play to our strengths, but not be slowed by our equipment and space limitations. On the one hand, we had 15 individuals capable of churning out a huge amount of work rather quickly; however, our department has only a single standing press that would accommodate the portfolio’s final dimensions. In our case, we made use of a modular structure composed of individual parts that could be fabricated by small teams and nipped in smaller presses, then assembled en-mass at the end. Before beginning work, we planned the entire project on paper, built prototypes, and received approval from the client. Templates of the individual parts of the portfolios were created during the design phase and, using these, all of the materials were first cut to size.

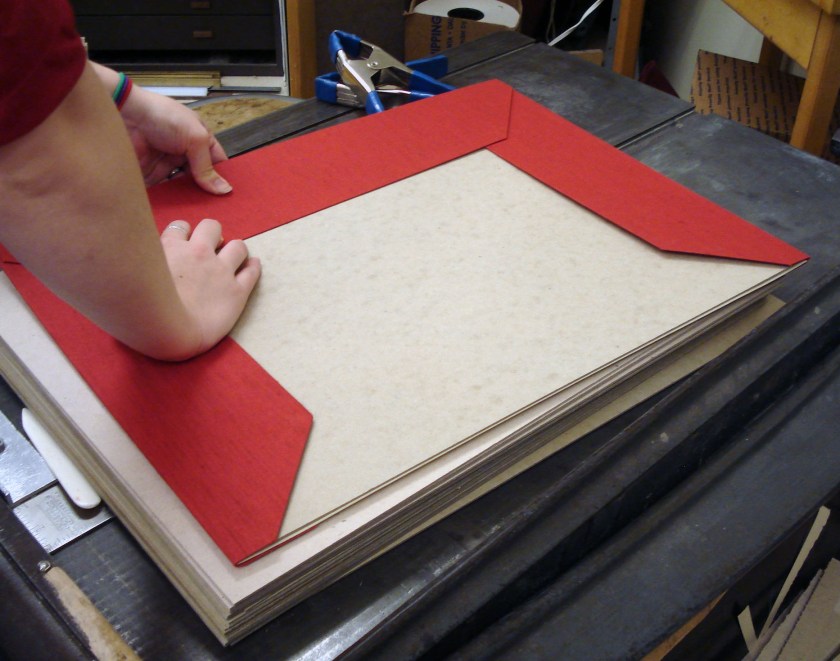

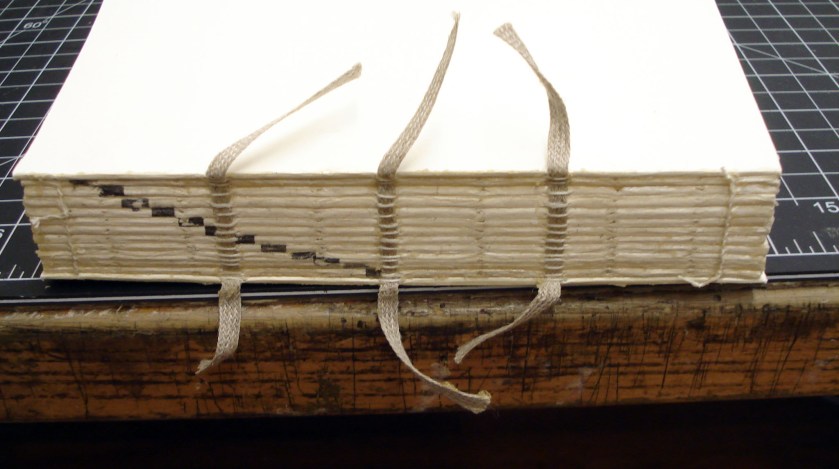

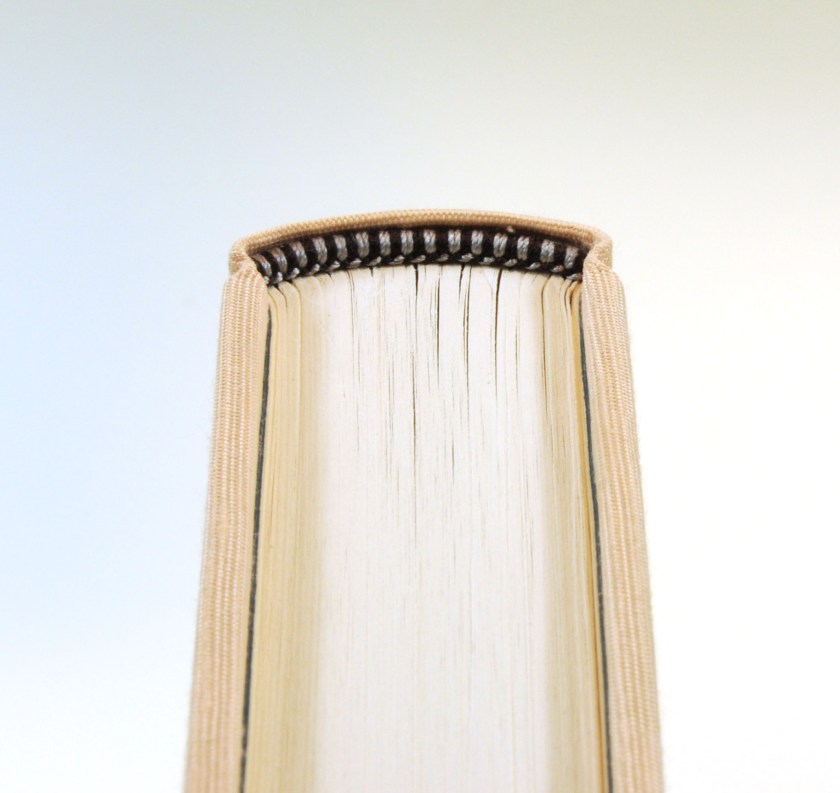

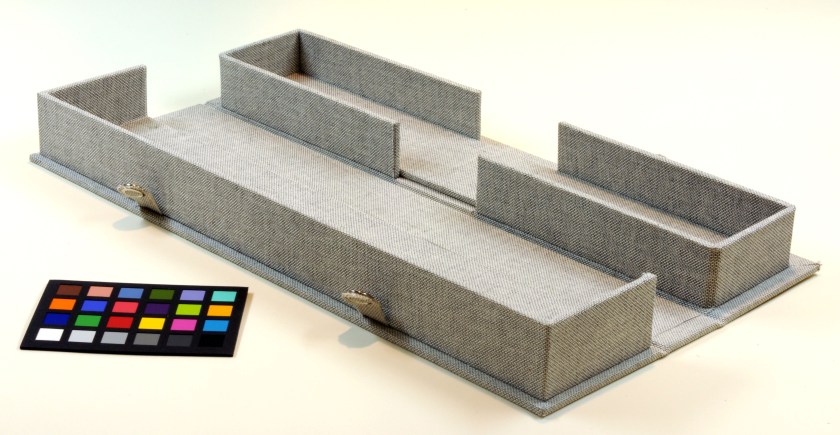

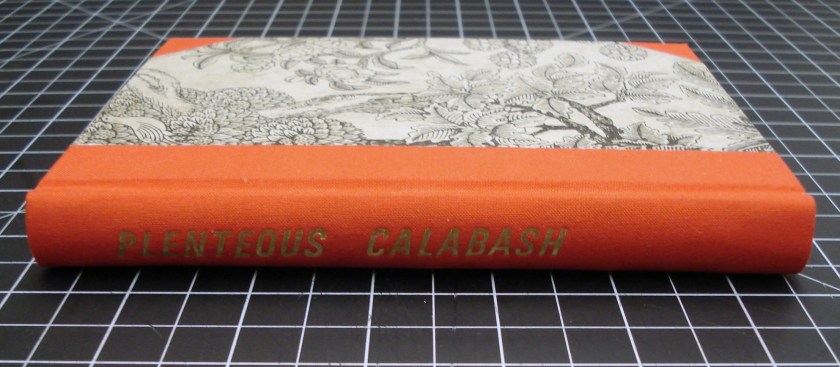

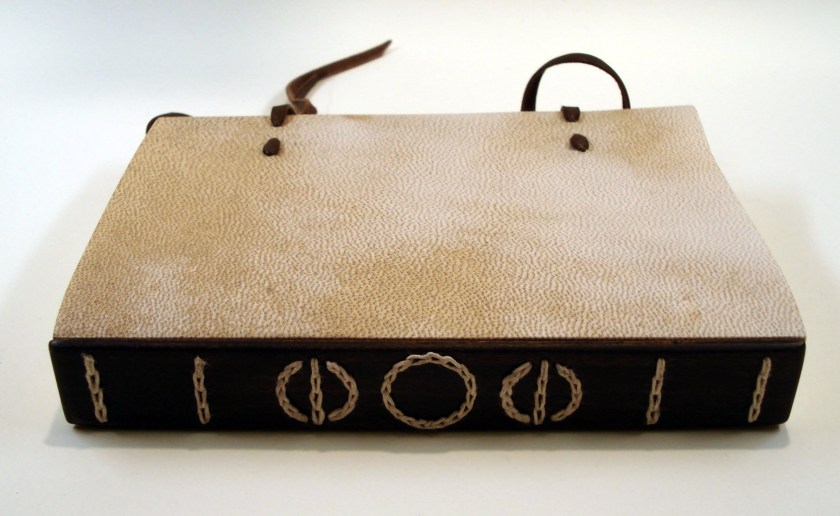

From these piles of individual parts, assembly began in stages. Three flaps of 20 pt board covered in red Canapetta book cloth were created to fit the head, tail, and fore-edge of each portfolio.

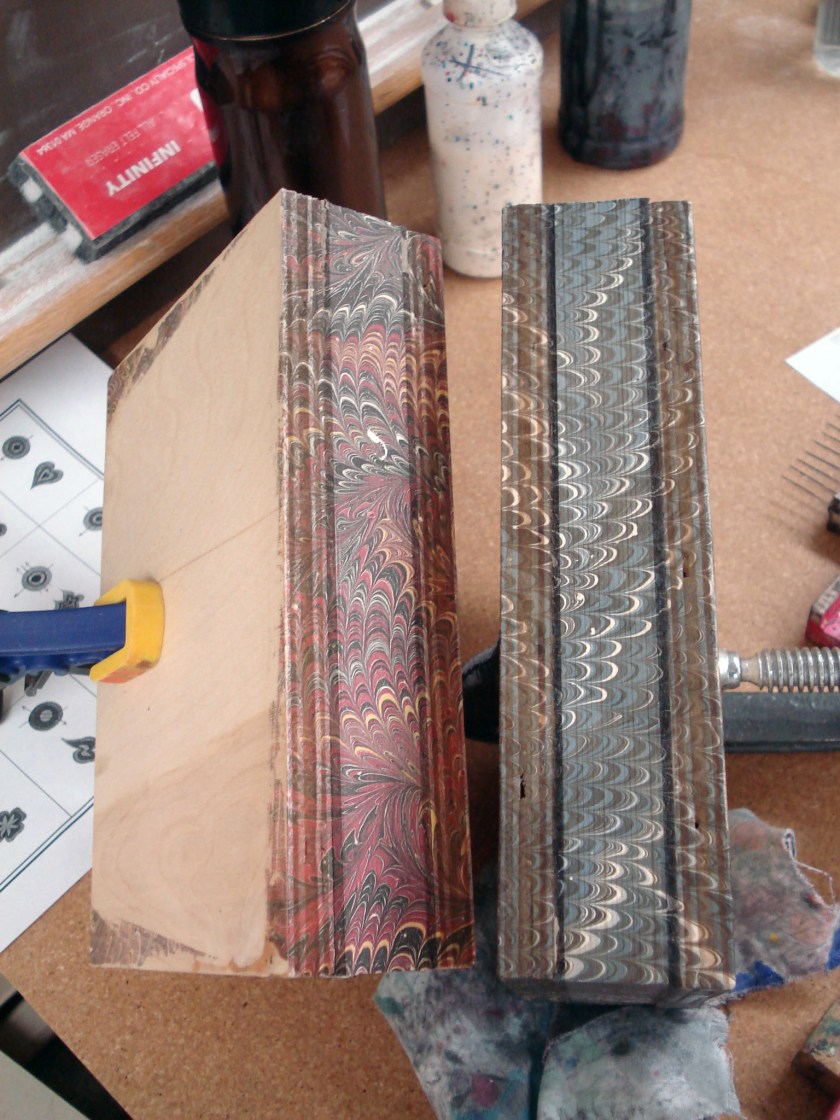

A separate team went to work constructing the back out of matte board and Nideggen, a mouldmade paper.

The flaps were attached to the back board, leaving enough joint space to accommodate the thickness of the set of prints.

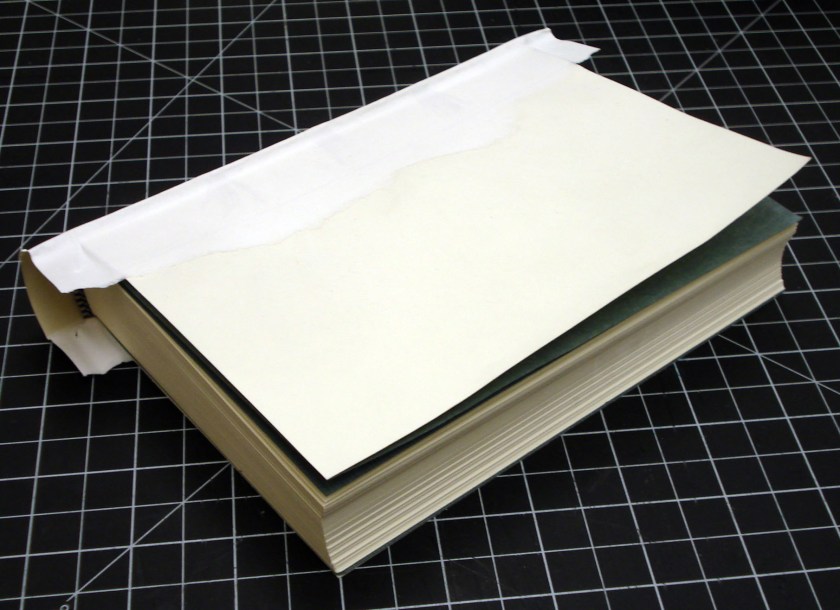

After placing a board of equal thickness to the prints inside the assembly…

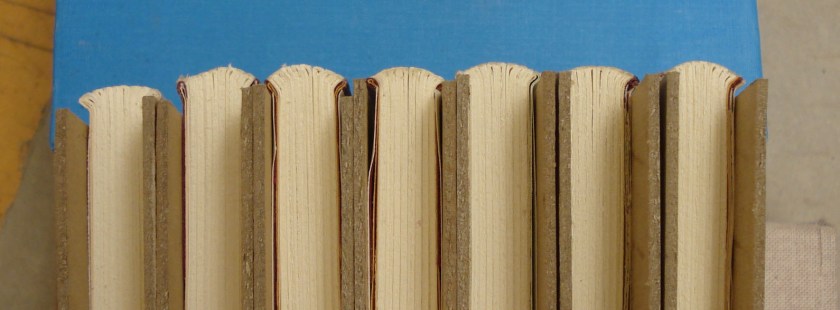

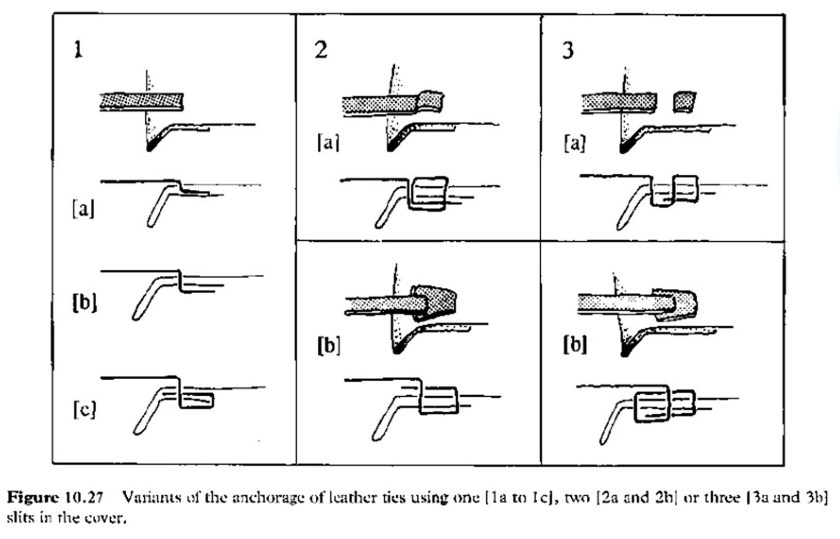

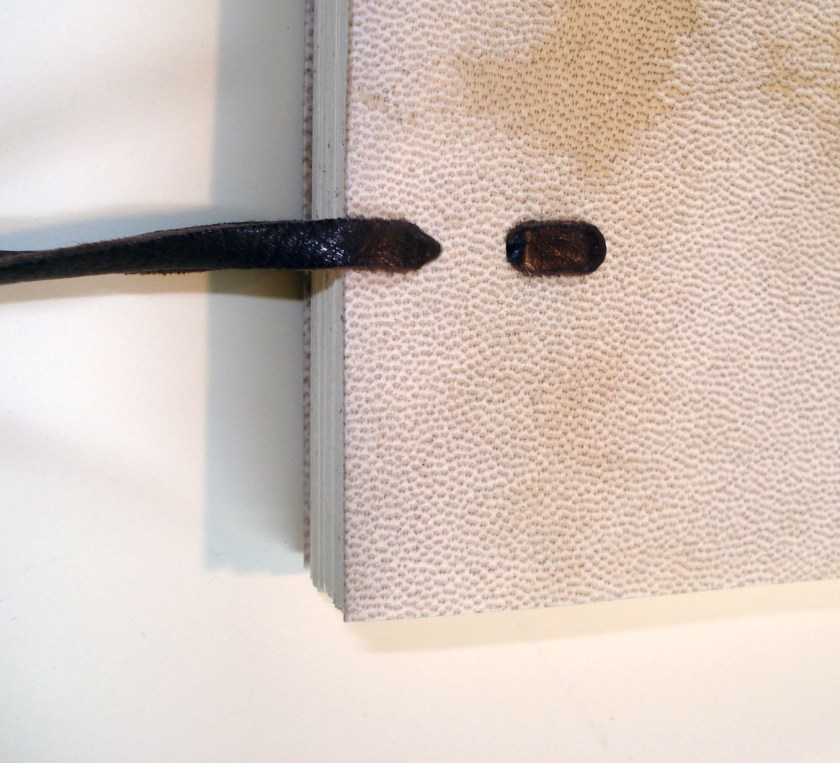

…the whole thing was put into the standing press. As the stack of “print trays” pressed and dried, we prepared the cases of the portfolios. A chisel was used to cut slots into the cover boards for lacing through the tying ribbons.

As the stack of “print trays” pressed and dried, we prepared the cases of the portfolios. A chisel was used to cut slots into the cover boards for lacing through the tying ribbons.

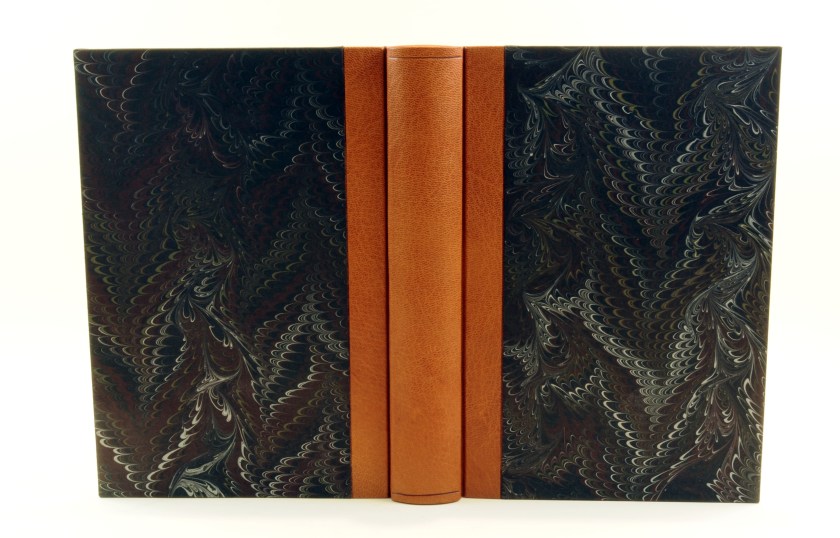

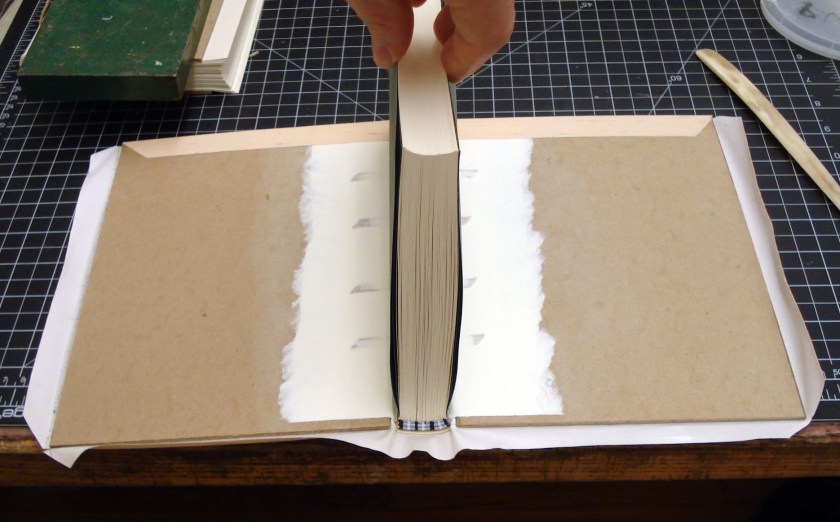

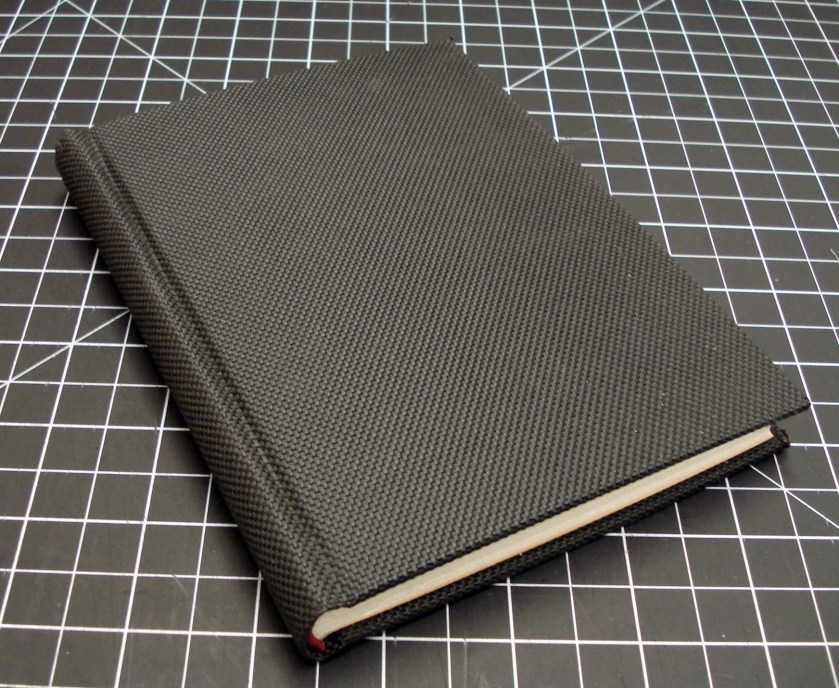

We then set up an assembly line for the case construction. Two students used foam rollers to give the boards a quick, even coat of PVA. Another student placed each board onto pre-cut cloth, using a jig to line them up and give consistent hinge space at the spine. After working the cloth down with a case folder and cutting the corners from the cloth, the cases were quickly nipped in the press.

We then set up an assembly line for the case construction. Two students used foam rollers to give the boards a quick, even coat of PVA. Another student placed each board onto pre-cut cloth, using a jig to line them up and give consistent hinge space at the spine. After working the cloth down with a case folder and cutting the corners from the cloth, the cases were quickly nipped in the press.

In the next stage, the ribbons were laced through the boards and the turn-ins were done.

In the next stage, the ribbons were laced through the boards and the turn-ins were done.

The inside hinge of the case was then finished off with a strip of cloth.

The inside hinge of the case was then finished off with a strip of cloth.

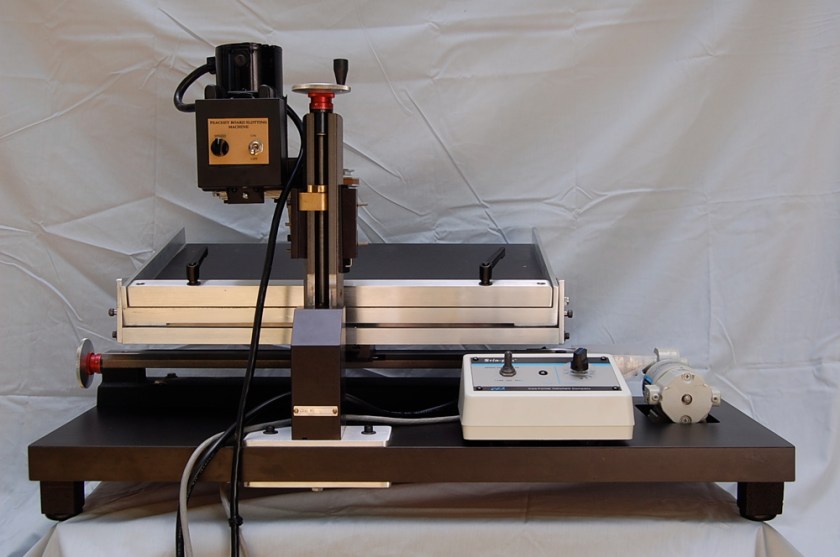

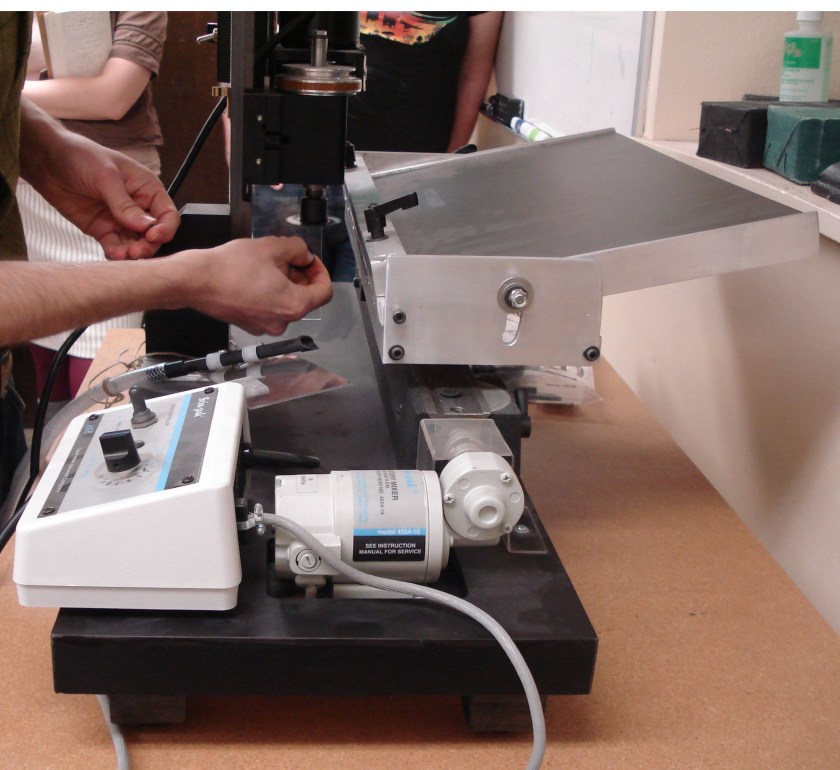

A custom die was made for carbon stamping the titling using the Kensol.

At this point, the two parts of the portfolios were ready to be assembled. The back of each print tray was glued out and carefully aligned in the case.

At this point, the two parts of the portfolios were ready to be assembled. The back of each print tray was glued out and carefully aligned in the case.

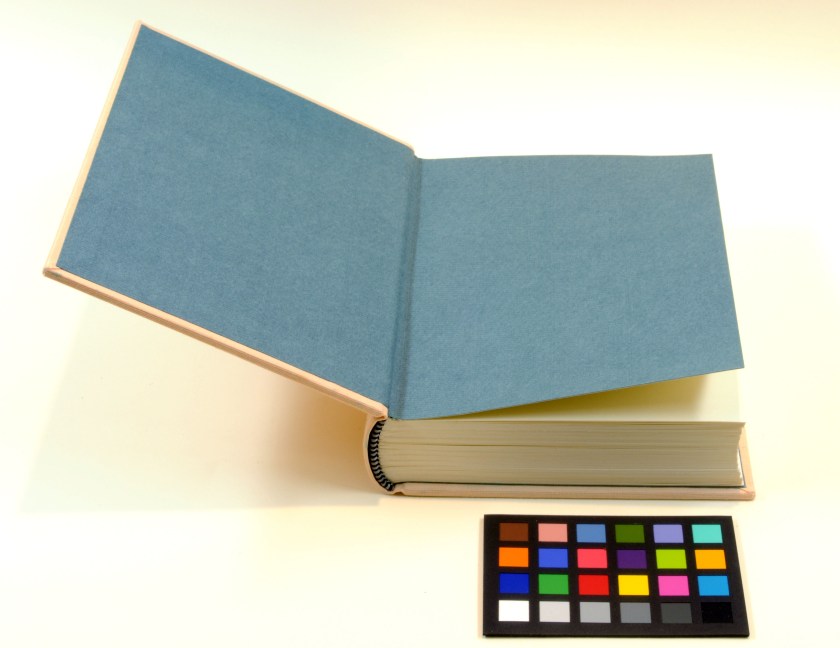

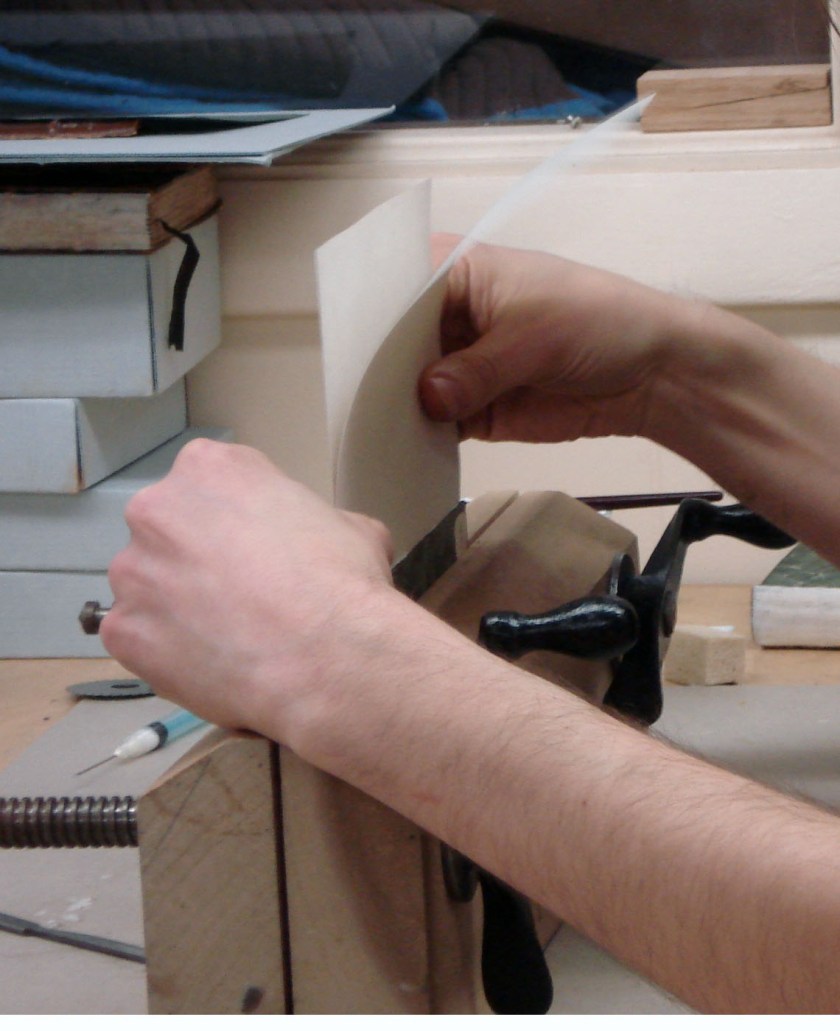

The portfolios were then nipped again between press boards to ensure a good bond between the tray and case. In the final step, the inside front board of the portfolio was trimmed out and finished with a Nideggen paste-down to match the tray back. Here I am, working quickly to glue out the paste-down. It’s somewhat comforting to know that, at NBSS, Tini Miura and Bill Anthony are always looking down upon you as you work.

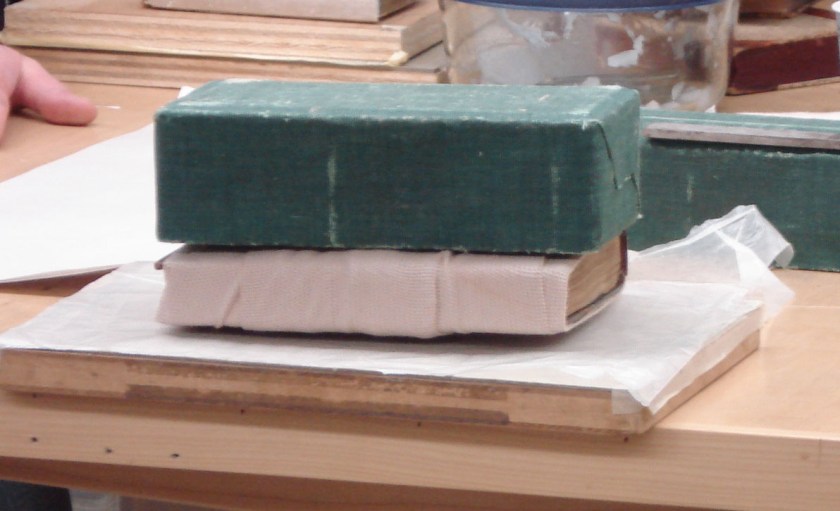

The portfolios were given a final press and allowed to completely dry under weight.

The portfolios were given a final press and allowed to completely dry under weight.

As a group, we had a lot of fun doing this project. Most of our curriculum is focused on individual work, and we don’t often get the chance to work together on a single project or develop our production methodology and technique. While we did not get to see the items that eventually went inside these portfolios, and we do not know where they will go or who will eventually own them, I like think that through this project and our intra-departmental collaboration, we were able to contribute to an international collaboration of craft.